Performers

Sol Gabetta cello

“Wit, aristocratic poise and elegance; mercurial shifts of mood, intensity and lightness of touch in near-miraculous balance.”

– The Glasgow Herald

Sol Gabetta achieved international acclaim upon winning the Crédit Suisse Young Artist Award in 2004 and making her debut with Wiener Philharmoniker and Valery Gergiev. Born in Argentina, Gabetta won her first competition at the age of ten, soon followed by the Natalia Gutman Award as well as commendations at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Competition and the ARD International Music Competition in Munich. A Grammy Award nominee, she received the Gramophone Young Artist of the Year Award in 2010 and the Würth-Preis of the Jeunesses Musicales in 2012.

Following her highly acclaimed debuts with Berliner Philharmoniker and Sir Simon Rattle at the Baden-Baden Easter Festival in 2014 and at Mostly Mozart in New York in August 2015, this season saw Gabetta debut with Los Angeles Philharmonic and Houston Symphony. She also performed with Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich and St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra. Brussels’s Palais des Beaux Arts also welcomeed her as their resident artist. To conclude 2015/2016 Gabetta joined the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra on a European tour with performances at Lucerne Festival, Grafenegg Festival as well as Salzburger Festspiele.

Gabetta performs with leading orchestras and conductors worldwide including the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Washington’s National Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Bamberger Symphoniker, Bolshoi and Finnish Radio Symphony orchestras and The Philadelphia, London Philharmonic and Philharmonia orchestras. She also collaborates extensively with conductors such as Giovanni Antonini, Mario Venzago and Krzysztof Urbański.

In summer 2014 Gabetta was Artist in Residence at the Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, having already held residencies at the Philharmonie and Konzerthaus Berlin. She is a regular guest at festivals such as Verbier, Gstaad, Schwetzingen, Rheingau, Schubertiade Schwarzenberg and Beethovenfest Bonn.

As a chamber musician Gabetta performs worldwide in venues such as Wigmore Hall in London, Palau de la Música Catalana in Barcelona and the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, with distinguished partners including Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Bertrand Chamayou. Her passion for chamber music is evident in the Solsberg Festival which she founded in Switzerland.

Sol Gabetta was named Instrumentalist of the Year at the 2013 ECHO Klassik Awards for her interpretation of Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto with Berliner Philharmoniker and Lorin Maazel. She also received the award in 2007, 2009 and 2011 for her recordings of Haydn, Mozart and Elgar Cello Concerti as well as works by Tchaikovsky and Ginastera. With an extensive discography with SONY she has also released a duo recital with Hélène Grimaud for Deutsche Grammophon.

Thanks to a generous private stipend by the Rahn Kulturfonds, Sol Gabetta performs on one of the very rare and precious cellos by Givanni Battista Guadagnini dating from 1759. Gabetta has taught at the Basel Music Academy since 2005.

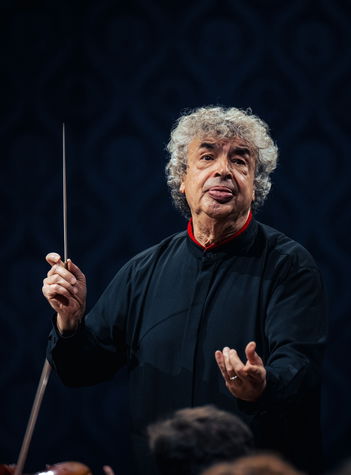

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Carnival Overture, Op. 92

“Whatever we have in Czech history that is truly great has grown from the bottom up!” This sentence by the famous Czech author Jan Neruda tells us a great deal about the history of the Czech nation and its great figures. It certainly applies unreservedly to Antonín Dvořák, whose growing artistry took him from a little village to the world’s greatest metropolises.

When Neruda wrote these words in 1884, he was 50 years old. And what was Antonín Dvořák doing in 1891 at age 50? He was a famous, sought-after composer, an artist whose popularity had long since crossed the borders of Austria-Hungary and spread all over Europe. It was in the year of his 50th birthday that he was offered the directorship of the National Conservatory of Music in New York. He considered the matter very carefully, consulting with many of the people who were close to him. For example, he wrote to his friend Alois Göbl in June 1891: “I’m supposed to go to America for two years! […] Should I accept the offer? Or not? Send me word.” Dvořák had never been very fond of celebrations, so it is no surprise that in early September he refused to take part in celebrations in Prague for his 50th birthday because he was spending time with his family at his beloved summer home in Vysoká, where he went to rest and to compose. Four days after his birthday (12 September 1891), he finished orchestrating Carnival Overture, Op. 92, the second work in a cycle of three concert overtures that are programmatic in character. We do not have a concrete programme from the composer, but he clearly realised something here that no one would have expected from him in the realm of symphonic music. Two years earlier, he had already gone down this path in chamber music with his Poetic Tone Pictures, Op. 85, thirteen pieces for solo piano, about which he jokingly commented: “I’m not just an absolute musician, but also a poet.” Dvořák had originally conceived his triptych of concert overtures depicting three aspects of human life as a single whole with the title “Nature, Life, and Love”. All three overtures are also carefully motivically interconnected. Ultimately, however, the composer told his publisher Simrock that his overtures “each can also be played separately”, and he gave them the opus numbers and titles In Nature’s Realm, Op. 91, Carnival Overture, Op. 92, and Othello, Op. 93. The first performance of all three overtures took place on 28 April 1892 at the Rudolfinum in Prague at the composer’s farewell concert before his departure for America, with Dvořák himself conducting the orchestra of the National Theatre. Dvořák also conducted their second performance, this time across the ocean on 21 October 1892 at New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Edward Elgar

Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85

The English composer Edward Elgar grew up in the family of a church organist who owned a shop that sold sheet music and instruments. Little Edward began playing the piano at school, and he learned to play the organ by watching his father. He also borrowed a variety of instruments from the family shop and taught himself to play them without receiving any kind of instruction, so he soon mastered not only piano and organ, but also violin, viola, cello, and bassoon. He also began composing in a similar manner. At age 16 he became a free-lance musician, so he got experience mainly as an instrumentalist, church organist, and conductor. He mostly composed choral music, but he did not achieve true renown as a composer until he reached the age of 42, when he wrote his Enigma Variations, Op. 36. The great conductor Hans Richter held the work in high esteem and prepared and led its premiere. The idea of creating a set of variations with a secret, “encoded” theme is indicative of Elgar’s unusual imaginativeness, and as a self-taught composer, he was not under any restraints. The work is a covert tribute to the composer’s wife Alice and to the friends who supported Elgar during the years of uncertainty as he got his start as a composer.

Another of Elgar’s most important works is the Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85. Just choosing the cello as a solo instrument represents a great challenge for composers. Antonín Dvořák may have put it most succinctly, once warning his composition pupils that unlike the piano or violin, which are capable of carrying themselves in front of an orchestra as ideal solo instruments, the cello does not possess comparable tonal qualities: “it whines up high and mumbles down low”. It is possible that after Elgar’s Violin Concerto (1907–1910), he was taking on a challenge as Dvořák had done—dealing with a difficult compositional task. The solutions the composer selected definitely hint at this. Elgar chose an unusual four-movement layout that differs from most other concertos and is more typical of chamber music, and Elgar’s concerto has a great deal in common with the chamber music genre. The composer deals with the cello’s sonic limitations by using a very delicate instrumental touch, and the music itself is in fact very personal, even intimate in character. Elgar’s musical language achieves perfection in its musical expression of pain and sorrow. The melancholy phrases that descend ever more deeply into despair and gloom are the key to the interpreter’s grasp of the entire work. The concerto dates from a time of great resignation immediately after the First World War. The composer himself was battling illness, but above all he was affected by the decline of his beloved wife’s health. She managed to attend the concerto’s premiere, but she died the following year. Although the premiere on 27 October 1919 featured the superb cellist Felix Salmond, the London Symphony Orchestra, and Elgar conducting, the performance did not turn out well because of a lack of sufficient rehearsal time. The failed premiere proved to be too much for the concerto. Despite the efforts of many outstanding cellists, it was not until 1965 that the work gained wide recognition thanks to the legendary recording made by Jacqueline du Pré, who was 20 years old at the time.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Symphony No. 4 in A Major (“Italian”), Op. 90

“My little room is now furnished, pictures hanging: Sebastian Bach above the piano, next to him Beethoven, and then several Raphaels – the decoration of the walls is quite varied. I also have a dressing table, with a bottle of eau de cologne, which all my aunts and cousins so admire. And then a tiny basket containing my three travel journals,” thus wrote Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847) in 1832 after returning to Berlin from a two-year journey to England, Scotland and Italy. Having Bach and Beethoven portraits in his apartment attests to the young composer’s musical loves and idols, while reproductions of Raphael’s paintings served to recollect his impressions of Italy. Mendelssohn’s keen interest in the history of art was kindled within the intellectual milieu in which he grew up. He was born in Hamburg, yet when he was three his family moved to Berlin in fear of Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. His grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn, was a renowned philosopher, a leading cultural figure who played a considerable role in the emancipation of Jews in German society. Felix’s father, the banker and art lover Abraham Mendelssohn renounced Judaism and converted to Protestantism, and also formally adopted another surname, Bartholdy. A musician herself, Felix’s mother Lea eagerly supported and nurtured her children’s talent. Felix grew up in a family romantically enchanted by Nature, poetry and music. He began composing at the time when music was perceived as capable of telling stories, conveying ideas and rendering impressions. Fully embracing this approach, his extensive oeuvre includes 12 early string symphonies, as well as five mature symphonies for full orchestra, combining the historical legacy with the Romantic sentiment of his time. Although not programme works, they clearly reflect Mendelssohn’s personal experience.

The most noteworthy of the mature symphonies are the third, the “Scottish”, and the fourth, the “Italian”, both inspired by the composer’s youthful travels. Mendelssohn began conceiving Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 90, the “Italian”, during his almost two-year sojourn in Italy, starting in May 1830. Carrying with him the travel diaries of Johann Wolfgang Goethe, who travelled through the country between 1786 and 1788, he visited Rome, Naples, Pompeii, Genoa, Milan, Venice, Florence and other places. In a letter to his sister Fanny, dated 22 February 1831, Mendelssohn wrote that he had been composing intensively, completing the cantata Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night), based on Goethe’s eponymous poem, adding that: “The Italian symphony is making great progress. It will be the most joyous piece I have ever done, the final movement in particular. I have not found anything for the adagio yet, and I think that I will save that for Naples.” He also pointed out: “Yet I still cannot get a grip on the Scottish symphony. Should during this time a good idea occur, I will snatch it, note it down presently and finish it.” Mendelssohn gave a secondary name to both symphonies. Completed in 1833, the Italian was performed on 13 May that year in London by the London Philharmonic Society, with the composer conducting. Not entirely satisfied with the work, Mendelssohn made revisions, yet he deemed none of them definitive, and so the piece exists in several versions. Chronologically, the Italian is actually his third symphony, as the composer only finished the Scottish in 1842, when it also received its premiere. The Italian was first published, posthumously, in 1851, thus having a higher number.

The first movement, in sonata form, reveals Mendelssohn as an innovator of the conventional conception. As against the bold main theme, the subsidiary theme is rather a mere episode, yet the development includes a third, contrapuntal, theme, attesting to the composer’s admiration of the Baroque masters. Created in response to the death of Mendelssohn’s teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832), as well as his beloved J. W. Goethe (1749–1832), the second movement too can be considered to be in sonata form, albeit without a development. The third movement is a minuet, while the finale incorporates the vivacious Saltarello, an Italian folk dance in 6/8 time.