1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Tokyo

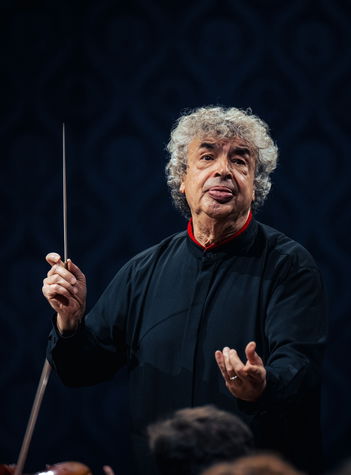

The Czech Philharmonic first ventured to Asia on a legendary tour in 1959. Since then, it has returned as often as every two years whenever possible. In fact, the orchestra has already performed 373 concerts in Japan. It discovered South Korea in the 1990s and made its debut in Taiwan in 2019. This time, the programme will feature works by Ravel, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky, Smetana, and Dvořák, led by Chief Conductor Semyon Bychkov.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

Performers

Anastasia Kobekina cello

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Performers

Anastasia Kobekina cello

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s brother Modest wrote that in the course of 1888, the composer’s “boldest dreams of fame were realised”. He had attained prosperity and universal esteem such as few composers enjoy in their lifetimes. “In his distrustfulness and modesty, he never stops being amazed and delighted that both abroad and in Russia, he receives more recognition than he could have expected. [...] He makes the impression of worldly happiness, and yet he his unhappier than ever before.” Tchaikovsky tried to escape his soul’s inner turmoil by busying himself with conducting engagements that were taking him from city to city and from one country to the next. “The thrill a composer feels when conducting an excellent orchestra playing his music with love and devotion was a new joy for me”, the composer confided. Prague was one of the cities where he received a real ovation: “From the first moment of my arrival, there were countless celebrations, visits, rehearsals, sightseeing etc. They were welcoming me as if I were a representative not of Russian music, but of all of Russia.” Tchaikovsky spent that summer working on his Fifth Symphony. Self-doubt never left him, however. “I want to work diligently to prove to myself and others that I have not yet completely written myself out. Doubts often come to me, and I wonder: is it not time for me to quit? Have I not yet exhausted my imagination?”, he wrote to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck.

There is no doubt that Tchaikovsky’s last three symphonies are works with programmatic subtexts, although there is no specific “plot” to speak of. The Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64, is built on the principle employed by Hector Berlioz in his pioneering Symphonie fantastique. Berlioz lets a single musical idea (idée fixe) run through the entire composition in various transformations, symbolising the composer’s beloved, his future wife Harriet Smithson. At the same time that Tchaikovsky was writing his Fifth Symphony, César Franck employed this same principle in his only symphonic work, the Symphony in D minor, likewise without assigning any concrete meaning to the unifying theme. The clarinet presents the central idea of Tchaikovsky’s penultimate symphony, a gloomy “fate” motif, in the introduction to the first movement. The composer merely hinted at the symphony’s programmatic content. About the first movement, he wrote: “Introduction – complete submission to fate. Allegro – dissatisfaction, doubts, complaints, reproaches”. In the second movement, fate yields to brighter tones, but it is not defeated, and its ominous presence makes itself felt even in the third movement, a light-hearted waltz. The fourth movement again opens with the “fate” motif, this time more distinctively structured, evoking a ceremonial atmosphere. This leads to conciliation expressed by the music of a majestic march, and in its ponderous strides, the burden of fate becomes an inherent part of existence. The struggle is not over, however; it leads to a new surge of energy as the symphony concludes at a fast tempo.

Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his Symphony No. 5 on 17 November 1888 in Saint Petersburg. It was a familiar scene for the composer: the audience responded with thunderous applause, while the critics remained divided, some calling the work a routine composition calculated for effect, while others hailed it as one of the most accomplished works of its era.