The concerts are dedicated to the memory of Soňa Červená.

Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children) moved the singer Fleur Barron the first time she heard them. “I have never felt that it is hard work to interpret or understand the content. It has always been perfectly clear to me. One can simply immerse oneself in Mahler's musical world—and for the listener, it is essential to surrender to it. Let these beautiful sound waves enter you and see what you experience. I perceive this music as an ocean of great strength.”

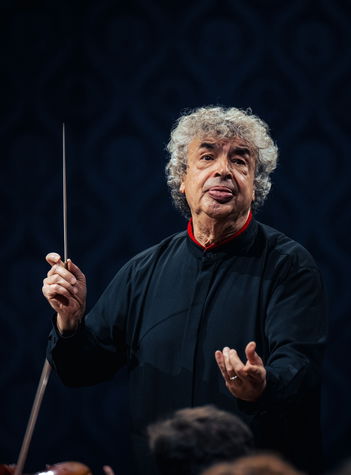

When Semyon Bychkov heard Mahler’s music for the first time as a student during a break between classes, when it was being played in one of the halls at the Mikhail S. Glinka Choir School, he was so thrilled by it that he forgot to return to class. His intense fascination with Mahler has lasted to the present day. Since 2022, he has been recording the complete Mahler symphonies with the Czech Philharmonic. “Something can’t be explained in words, but it is possible to feel it. And I feel that this is the perfect orchestra for the music of Gustav Mahler”, says our current chief conductor.

“Discovering Mahler’s music is like discovering life itself. Experiencing it means being drawn into his world and values. What arises from his music, letters, and the testimony of those who knew him is the duality of this man. As a creator and, at the same time, an interpreter, he invents sounds that recreate the world of nature and people. He had less than 51 years to become aware of the fundamental questions of our existence, and even less time to answer them. Still, it was long enough for him to express the polyphony of life: its nobility and banality, its reality and its otherworldliness, its childlike naiveté and its inherent tragedy”, says Maestro Bychkov.

Bychkov gives the music of Richard Wagner a surprising description: Buddhistic. He says his operas have no beginning or ending, and that normal time seemingly does not exist in them. We will be able to put that assertion to the test in the overture to Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Bychkov has conducted the opera at London’s Covent Garden and elsewhere. For Lohengrin he won the award from the BBC Music Magazine for the best recording of 2010. Currently, he is in the middle of a cycle at Bayreuth with Tristan und Isolde. In other words, he is a Wagner specialist.

The first performance of Tannhäuser Overture separate from the opera was given in 1846 by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, whose joyous Italian Symphony opens the concert.

Performers

Fleur Barron mezzo-soprano

“I think I’m drawn to these types of projects—ones that are meaty and have something to say, that

are not just musically beautiful and engaging but also somehow related to what life is about today”,

says mezzo-soprano Fleur Barron, referring to, among other things, the opera Adriana Mater by Kaija

Saariaho; her performance of the lead role in that work recently earned her a Grammy. The singer of

Singaporean and British origin, whose mentor has been Barbara Hannigan for many years, is now

dividing her career between opera, concert appearances, and chamber or solo recitals. Rather then

simply a means of conveying beauty, music for her is also a medium with possibilities for a far greater

reach, as is shown by some of her projects aimed at bringing divergent cultures together.

She grew up in a very culturally diverse environment. Born in Northern Ireland, she spent most of her

childhood in Hong Kong. She moved to New York with her parents while in her teens, and there she

was thrilled by a show on Broadway. Back then, she thought opera was “boring”, but she changed

her opinion after she began joining her classmates to attend Metropolitan Opera performances with

student tickets. After earning a bachelor’s degree in comparative literature at Columbia University,

she began to look into serious vocal studies, and the result was a master’s degree from the

Manhattan School of Music. Getting started was not easy, however: “My masters was very tough for

my ego because I was way behind the curve compared to everybody else, and that was a challenge”,

she said. “I was used to being good at things, and suddenly I felt way behind. Unlike most things

where you feel behind, you can just work harder and you get better. With singing it’s really not like

that because the harder I tried, the more tense I would get. So it was a long journey.”

In the end, however, the long journey was successful, and we now find Fleur Barron appearing with

the world’s top orchestras (Berlin Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Bavarian Radio Symphony

Orchestra etc.) and leading conductors (Esa-Pekka Salonen, Daniel Harding, Kent Nagano, Nathalie

Stutzmann, and Kirill Petrenko); as part of a concert tour, she made her debut with the Czech

Philharmonic and its chief conductor Semyon Bychkov. Recently, she has been seen frequently on

stage in the Mahler repertoire, but music of the 20th and 21st centuries is no exception, for example,

and her operatic repertoire reaches as far back as the Baroque period (e.g. Monteverdi’s Il Ritorno

dʼUlisse in Patria). At recitals, she is most frequently accompanied by Julius Drake (for example, in

the 2024/2025 season they appeared together at London’s Wigmore Hall and in Amsterdam,

Stuttgart, and Madrid), but she recently gave her Carnegie Hall debut with the pianist Kunal Lahiry,

with whom she undertook a whole American tour. She is also an artistic partner of the Orquesta

Sinfónica del Principado de Asturias in Oviedo, Spain.

Alongside her performing career, she also gives many masterclasses each year, for example at

Harvard, the Manhattan School of Music, the Royal Academy of Music, and London’s King’s College.

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

Symphony No. 4 in A Major (“Italian”), Op. 90

“My little room is now furnished, pictures hanging: Sebastian Bach above the piano, next to him Beethoven, and then several Raphaels – the decoration of the walls is quite varied. I also have a dressing table, with a bottle of eau de cologne, which all my aunts and cousins so admire. And then a tiny basket containing my three travel journals,” thus wrote Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847) in 1832 after returning to Berlin from a two-year journey to England, Scotland and Italy. Having Bach and Beethoven portraits in his apartment attests to the young composer’s musical loves and idols, while reproductions of Raphael’s paintings served to recollect his impressions of Italy. Mendelssohn’s keen interest in the history of art was kindled within the intellectual milieu in which he grew up. He was born in Hamburg, yet when he was three his family moved to Berlin in fear of Napoleon Bonaparte’s army. His grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn, was a renowned philosopher, a leading cultural figure who played a considerable role in the emancipation of Jews in German society. Felix’s father, the banker and art lover Abraham Mendelssohn renounced Judaism and converted to Protestantism, and also formally adopted another surname, Bartholdy. A musician herself, Felix’s mother Lea eagerly supported and nurtured her children’s talent. Felix grew up in a family romantically enchanted by Nature, poetry and music. He began composing at the time when music was perceived as capable of telling stories, conveying ideas and rendering impressions. Fully embracing this approach, his extensive oeuvre includes 12 early string symphonies, as well as five mature symphonies for full orchestra, combining the historical legacy with the Romantic sentiment of his time. Although not programme works, they clearly reflect Mendelssohn’s personal experience.

The most noteworthy of the mature symphonies are the third, the “Scottish”, and the fourth, the “Italian”, both inspired by the composer’s youthful travels. Mendelssohn began conceiving Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 90, the “Italian”, during his almost two-year sojourn in Italy, starting in May 1830. Carrying with him the travel diaries of Johann Wolfgang Goethe, who travelled through the country between 1786 and 1788, he visited Rome, Naples, Pompeii, Genoa, Milan, Venice, Florence and other places. In a letter to his sister Fanny, dated 22 February 1831, Mendelssohn wrote that he had been composing intensively, completing the cantata Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night), based on Goethe’s eponymous poem, adding that: “The Italian symphony is making great progress. It will be the most joyous piece I have ever done, the final movement in particular. I have not found anything for the adagio yet, and I think that I will save that for Naples.” He also pointed out: “Yet I still cannot get a grip on the Scottish symphony. Should during this time a good idea occur, I will snatch it, note it down presently and finish it.” Mendelssohn gave a secondary name to both symphonies. Completed in 1833, the Italian was performed on 13 May that year in London by the London Philharmonic Society, with the composer conducting. Not entirely satisfied with the work, Mendelssohn made revisions, yet he deemed none of them definitive, and so the piece exists in several versions. Chronologically, the Italian is actually his third symphony, as the composer only finished the Scottish in 1842, when it also received its premiere. The Italian was first published, posthumously, in 1851, thus having a higher number.

The first movement, in sonata form, reveals Mendelssohn as an innovator of the conventional conception. As against the bold main theme, the subsidiary theme is rather a mere episode, yet the development includes a third, contrapuntal, theme, attesting to the composer’s admiration of the Baroque masters. Created in response to the death of Mendelssohn’s teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832), as well as his beloved J. W. Goethe (1749–1832), the second movement too can be considered to be in sonata form, albeit without a development. The third movement is a minuet, while the finale incorporates the vivacious Saltarello, an Italian folk dance in 6/8 time.

Gustav Mahler

Kindertotenlieder

In 1901 and 1902, Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) wrote, almost concurrently, two works to poems by Friedrich Rückert (1788–1866): the set of five songs Rückert-Lieder and the Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children), two of the most magnificent song cycles there are. Rückert was the founder of Oriental studies in Germany (he even translated a part of the Quran) and a distinguished poet, whose verse inspired numerous composers. In the Kindertotenlieder, he vented his grief over the loss of both his children, who died of scarlet fever within a mere three weeks at the turn of 1834. Rückert outpoured his deep sorrow in a collection of more than 400 poems (only published posthumously, in 1872). Mahler’s cycle is sometimes construed as an expression of his anticipating that a similar tragedy would one day befall him – and indeed, in 1907 he and his wife Alma lost a daughter. Mahler composed three of the songs back in 1901, and the remaining ones in 1904, shortly after the birth of their second daughter. Mahler’s anxieties were rooted in the trauma of seeing most of his siblings pass away during their childhood, with the death of a brother two years his junior having struck him most profoundly.

The Kindertotenlieder premiered on 29 January 1905 at a concert held at the small hall of the Musikverein in Vienna by the Vereinigung schaffender Tonkünstler (Society for Creative Musicians), with Mahler, its honorary president, conducting. The soloist was Friedrich Weidemann (1871–1919), a leading baritone at the Hofoper. “With a lucky hand, Mahler selected the five most beautiful of the poems, immersing them in tones of a deeply dolorous, yet always tender, simple and restrained feeling. No black-framed mourning notice with impassioned words, only the heart bearing an invisible funeral veil. [...] In Mahler’s songs the bewailing father withholds tears with dignity. The sky is not hopelessly gloomy, a warming ray of love shines through,” the Austrian music critic Julius Korngold wrote in the wake of the premiere. On 3 February 1905 the concert was repeated, and that June Weidemann performed the songs again, in Graz. Another major early interpreter of Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder was the Dutch baritone Johan Messchaert (1857–1922), who presented it (with piano accompaniment) on 28 January 1907 in Vienna and on 14 February 1907 in Berlin. Not all responses to the cycle were laudatory. Driven in part by the rising local anti-Jewish sentiment, some harboured a grudge against Mahler, found fault with his work as the Hofoper’s director, denounced his music as overly eccentric. In consequence of this hostile atmosphere, the composer ultimately left Vienna. He would only return to the Habsburg capital four years later – to die.

Richard Wagner

Tannhäuser, overture to the opera

The second half of tonight’s concert comprises a work by Richard Wagner (1813–1883), a prolific and celebrated composer, a genius whose legacy is, however, stained by his anti-Semitic writings. Much has been said of his infamous pamphlet Judenthum in der Musik (Jewishness in Music), first published under a pseudonym in 1850 in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik and republished in 1869, this time independently, under Wagner’s name, with an expanded commentary explaining the author’s radical views. Within the still continuing debates, Wagner’s defenders have mentioned his personal motives, pointed out the Jewish artists he revered and collaborated with, but some of his egregious words simply cannot be shrugged off. In 1842, Wagner was appointed Kapellmeister at the Hoftheater in Dresden. “On Maudy Thursday of my first year in Dresden [1843], Mendelssohn arrived in town in order to conduct his oratorio Paulus. On this occasion, greatly impressed by the piece, I attempted to re-establish cordial relations with Mendelssohn,” Wagner wrote in his autobiography. The two artists knew each other from Leipzig and their paths crossed quite a few times. In Dresden, they disagreed on the tempos at which Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 should be performed. Yet in the light of Wagner’s anti-Jewish pamphlet, this purely professional dispute assumes entirely different dimensions. Mahler, for his part, was familiar with Wagner’s squalid essay. Even though he himself faced anti-Semitism in Vienna, which significantly grew during Mayor Karl Lueger’s tenure (1897–1910), Mahler was the first to conduct at the Hofoper (in 1899) Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg in its entirety, which even silenced the malevolent press. These randomly mentioned examples serve to raise the eternal question of whether it is possible (and appropriate) to separate an oeuvre from its creator.

Tannhäuser und der Sängerkrieg auf Wartburg (Tannhäuser and the Minnesängers’ Contest at Wartburg) is the first of Wagner’s operas based on German or Norse legends. “By May of my thirtieth year I had finished my poem Der Venusberg [The Mount of Venus], as I referred to Tannhäuser at the time. I had not by any means yet garnered any real knowledge of Medieval poetry,” the composer noted in his autobiography. The earliest written accounts of the story of the knight Tannhäuser, Venus and her grotto in the Venusberg, as well as Tannhäuser’s penitent pilgrimage to Rome, date from the 15th century. The legend was first published in 1515 in Nuremberg. In his opera, Wagner connected the myth with a plot from a 13th-century collection of German poetry, involving a minstrel contest at the Wartburg castle in Thuringia. From 1841 to 1843, he worked on the libretto, with some of it conceived in the spa of Teplitz (Teplice, Bohemia). He completed the full score in May 1845. Half a year later, on 19 October, Tannhäuser premiered at the Hoftheater in Dresden. The first to perform the title role was the Czech tenor Josef Alois Ticháček (Tichatschek, 1807–1886). Wagner would make several revisions to the opera. He applied particularly distinct changes to the piece for a performance at the Paris Ópera, believing that a triumph there would afford him a great opportunity to re-establish himself following his exile from Germany, yet the production was soon withdrawn from the repertoire. Czech music lovers would first get to see a performance of Tannhäuser on 25 November at the Estates Theatre in Prague, conducted by František Škroup. The opera was first presented in Czech on 16 January 1888 at the Municipal Theatre in Pilsen (Plzeň). The Overture to Tannhäuser, the last part of the work completed, has been performed independently in concert. Structured in sonata form, through the Pilgrims’ Chorus and the erotic allurement of the Venusberg it sums up the main theme of the opera, conveying the contrast between carnal earthly and pure chaste love.