1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Mao Fujita

It has been 80 years since the end of the Second World War and 50 since the death of Shostakovich. In commemoration of both, we will hear the composer’s Eighth Symphony, performances of which were banned in the Soviet Union because of its bleakness. First, however, making his return to the Rudolfinum in Strauss’s Burleske is Mao Fujita, whom critics call a rising world-class pianist.

Programme

Richard Strauss

Burlesque for piano and orchestra in D minor, TrV 145 (17')

— Intermission —

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Op. 65 (61')

Performers

Mao Fujita piano

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Whenever you need to purchase a wheelchair-accessible ticket.

This concert will be broadcast live on medici.tv and on October 11 at 9 p.m. on Mezzo Live.

![]()

![]()

“I feel eternal pain for those who were killed by Hitler, but I feel no less pain for those killed on Stalin’s orders. I suffer for everyone who was tortured, shot, or starved to death. There were millions of them in our country before the war with Hitler began. The war brought much new sorrow and much new destruction, but I haven’t forgotten the terrible pre-war years. That is what my symphonies are about, including Number Eight.”

– Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich

It is no wonder that Shostakovich preferred to discuss his Eighth Symphony publicly only as an attempt to depict the tragedy of the Second World War, which took the lives of millions of Russians. The work’s gloomy mood was ill suited for the Soviet regime’s propaganda. The symphony was withdrawn from the repertoire, and it was officially banned in 1948. It did not return to concert halls until eight years later.

Richard Strauss’s Burleske for piano and orchestra did not have an easy time reaching listeners either. The young composer wrote the work originally titled Scherzo in D minor in 1886 for the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow, who had secured the still youthful Strauss a conducting post with the Meiningen Court Orchestra.

Bülow, however, called the work unplayable and refused to learn it. Ultimately, the composer himself played the solo part in Meiningen. The work waited three years for its next performance, when the pianist Eugen d’Albert persuaded Strauss to simplify the piece, earning the dedication of the revised version of the Scherzo, now with its new title Burleske.

This is not the first encounter between the Japanese pianist Mao Fujita and the Czech Philharmonic. In 2023, he took part in a tour of Asia with the orchestra and Semyon Bychkov. He again played Dvořák’s Piano Concerto under Jakub Hrůša’s baton at the BBC Proms at Royal Albert Hall in August 2024. A month later, he gave a recital at Prague’s Rudolfinum.

Performers

Mao Fujita piano

With an innate musical sensitivity and naturalness to his artistry, 26-year old pianist Mao Fujita has already impressed many leading musicians as one of those special talents which come along only rarely, equally at home in Mozart as the major romantic repertoire.

Born in Tokyo, he began piano lessons at the age of five and won his first international prize in 2010 at the World Classic in Taiwan. While still studying at the Tokyo College of Music in 2017, he took First Prize at the prestigious Concours International de Piano Clara Haskil in Switzerland, which brought him to the attention of the international music community for the first time. He was also the Silver Medalist at the 2019 Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow.

Fujita has been invited to appear in recital at major international festivals and made US recital debut at Carnegie Hall in January 2023. Recent orchestral highlights include performances with the Gewandhausorchester, Munich Philharmonic, Royal Philharmonic or Royal Concertgebouw. In November 2021, Fujita signed an exclusive multi-album deal with Sony Classical International (Mozart’s complete piano sonatas, 72 Preludes by Chopin, Scriabin, and Yashiro). He is a member of Konzerthaus Dortmund’s series "Junge Wilde" from the 24/25 season.

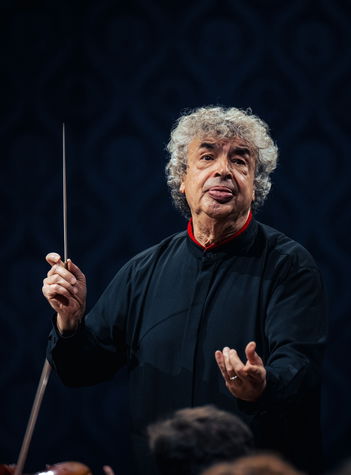

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Richard Strauss

Burleske for piano and orchestra in D minor, TrV 145

A rebel of musical forms, a pioneer of modern harmony, and a master of the symphonic poem, Richard Strauss (1864–1949) was as a kindred spirit of Gustav Mahler and an admirer of Johannes Brahms in his youth and of Richard Wagner in the later years of his successful composing and conducting career.

Strauss was never particularly drawn to composing works for piano and orchestra. He actually wrote only three including pair of works from 1925 and 1928 associated with the famed Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm during the First World War. It was he who commissioned the first of these concertos from Strauss—the Parergon on Sinfonia domestica. The Greek word parergon means a work that is a byproduct or supplement, and it is, in fact, based on musical material from Strauss’s successful 1904 symphonic poem describing daily life in his household. Wittgenstein also premiered the other concerto titled Panathenäenzug (Panathenaic Parade), but the best known and most popular of Strauss’s piano works turned out to be a work he had written a full four decades earlier.

Strauss composed his Burleske in 1885 while employed in the Thuringian town Meiningen as the assistant conductor under Hans von Bülow, an important composer, conductor, and pianist who was Strauss’s mentor and gave him significant support early in his career. It was to him that Strauss dedicated his Burleske, originally titled Scherzo in D minor, but Von Bülow refused to learn it, regarding it is technically unplayable and too “Lisztian”. Strauss attempted to play the piano part himself, but after the first rehearsal with orchestra, he set the work aside. He returned to it a few years later and offered it to the pianist Eugen d’Albert, who was impressed by the Burleske and performed it in 1892 after some minor revisions by the composer.

In October 1885, Johannes Brahms premiered his Fourth Symphony in Meiningen. For the young Strauss, witnessing this extraordinary moment was something of a formative experience. Of all of the influences on Strauss at the time, that of Brahms is therefore the most apparent in the Burleske. In the composition in one movement lasting about 20 minutes, dramatic sections alternate with playfully melodic passages. The music makes a fresh, virtuosic impression, and it gives the performer room to demonstrate technical perfection and sensitivity for mood and expression. In terms of its form, however, the Burleske aligns itself more with the legacy of the symphonic poem and foreshadows Strauss’s further development as the composer who would develop that musical genre to unprecedented dimensions.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Op. 65

During the Second World War, Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975) composed three symphonies. He wrote his Ninth in 1945, between the war’s end in Europe and its conclusion in the Pacific. At the premiere on 3 November, Stalin had expected a grandiose work with chorus and vocal soloists, but instead Shostakovich presented a symphony that was shorter than the first movement of either of its two predecessors, that was optimistic, and that formally and sonically resembled the classical symphonies of Mozart. It is not as intellectually weighty as its two predecessors, nor is it by any means as monumental as the famous “Ninths” by Beethoven or Mahler. The composer said he started thinking about the Seventh before the war had begun, but most of it was written in the last months of 1941. In September, German troops besieged Leningrad, and Shostakovich’s native city and its inhabitants remained under a cruel and devastating blockade for 872 days. That October, Shostakovich and his family were evacuated to Kuybyshev (now Samara), he finished the symphony in December, and it was premiered in early March. A few months later, on 9 August 1942, the Seventh was also heard in Leningrad itself under dramatic circumstances thanks to the enormous personal efforts of everyone involved. The work quickly got the name Leningrad Symphony and became a symbol of Russia’s indomitable spirit, determination, and resistance to Nazism.

Shostakovich escaped the horrifying conditions in besieged Leningrad, but the war itself remained present in his life. Immediately after the June invasion, he volunteered repeatedly to join the army, but the officials and commissars turned him down each time so he could devote himself to his civilian vocation, so he gave concerts, composed, and taught at the conservatoire, where he patrolled the roof as a volunteer fireman. After finishing his Seventh Symphony, he said he wanted to begin composing an oratorio about the heroic defenders of Moscow, an opera, and a ballet. In the end, however, he channelled his energies into work on another symphony written during the summer of 1943, which he spent in the city Ivanovo north of Moscow. “In recent days, I finished work on my new Eighth Symphony. I wrote it rather quickly, in a bit over two months. […] It lacks any kind of narrative. It just reflects my thoughts and experiences and my reactions to joyous news about victories of the Red Army. This new work of mine is a peculiar attempt to gaze into the future, into the post-war era”, Shostakovich wrote on 18 September for the weekly journal Literature and the Arts.

That February, the Soviet army had been victorious at Stalingrad, and as a Soviet composer he was expected to write a symphony that was celebratory and heroic. Notwithstanding the composer’s public proclamations, his Eighth is nothing of the kind. Against the backdrop of great battlefield victories, Shostakovich saw not triumph, but millions of ruined lives, despair, and the futility of a war that was corroding both society and the individual from within. During the Great Terror of the 1930s, Stalin had many of Shostakovich’s friends executed, and the composer spent nearly his whole life in fear that he would meet a similar fate. Having become popular in the West as well, especially after the success of the Leningrad Symphony, Shostakovich sometimes enjoyed the protection of the regime, but at other times he suffered criticism, threats, and humiliation. He therefore became a master of irony. He said one thing while thinking something else, but it was through his music that he could be the most sincere. That is what the Eighth Symphony is like: here ironic, there sincere, and at times even absurd, just as war and living in wartime seemed absurd to Shostakovich.

Shostakovich characterised his Eighth as a work full of dramatic internal conflicts. This applies both to its philosophical meaning and to the music itself. The first movement is characteristic in this regard, beginning at a slow tempo and in a gloomy mood, alternating in places with lyrical episodes for the woodwinds. One of the longest movements in any of Shostakovich’s symphonies, it reaches its climax around its midpoint, when a gradual crescendo arrives at a powerful forte Allegro. The seemingly chaotic sound of the roaring orchestra is put into order by a strong but irregular march rhythm. The first movement ends slowly and quietly, but the music’s character remains more threatening than conciliatory. The threat becomes reality in the second, third, and fourth movements. Each is a march in its own way—the second with ironic elements in a dance-like scherzo, and the fourth like a dark, sluggish funeral march. A certain calming and catharsis finally arrives with the concluding Allegretto in the form of lyrical melodic passages and pastoral motifs, but here, too, there is no lack of dramatic episodes, and even the lyrical-sounding conclusion in C major is haunted by dark echoes in the contrabass. “I can express the philosophical idea of my new work very briefly in just three words: life is beautiful. All that is evil and ugly will disappear, and beauty will triumph”, Shostakovich wrote in Literature and the Arts. It is up to everyone who listens to the Eighth Symphony to judge how ironically or sincerely those words were meant.