Performers

Augustin Hadelich violin

The life of Augustin Hadelich is the story of a prodigy from a farm in Tuscany who has managed to rise to the very summit among today’s most important performers worldwide. He was born in the Italian town Cecina (not far from Livorno) to German parents who owned a farm there. He began playing the violin at age five (his two brothers were already playing cello and piano at home) under the guidance of his father, an amateur cellist, who long remained his only teacher apart from a couple of famous violinists (Norbert Brainin and Uto Ughi) who travelled to Tuscany to spend the summer and were also willing to give Augustin lessons. They recognised his great talent, so Hadelich began studies at the Istituto Mascagni, a conservatoire in nearby Livorno. Later, he was admitted to the prestigious Julliard School, where he studied under Joel Smirnoff.

He began his performing career at age 22, when he won the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis (2006). Since then, music critics have been showering him with superlatives for his phenomenal technique, stunning tone colour, and thoughtful interpretations. He finds subtle nuances in compositions, and he does not hesitate to experiment, as he showed in his solo Bach recording, for which he used a Baroque bow to achieve the ideal sound. He is also unafraid to perform contemporary music. In fact, his recording of Dutilleux’s Violin Concerto won a 2016 Grammy.

His concert and recording credits also include many works of the traditional repertoire, such as the Dvořák Violin Concerto on today’s programme, which can be heard on Hadelich’s CD “Bohemian Tales” with Jakub Hrůša and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, for which Hadelich won the 2021 Opus Klassik prize and earned a Grammy nomination, which he did not win in this case, although critics praised his ability to tell a story through music, to present an interpretive statement with confidence, or to devote great attention to small details of articulation.

His career races ahead at a hectic pace so the pure sound of his violin, a 1744 Guarneri, will be heard in the world’s most important concert halls. His partners on his musical pilgrimages include America’s most important orchestras as well as the Berlin Philharmonic, the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Tokyo. Hadelich also teaches violin at Yale University and gives masterclasses.

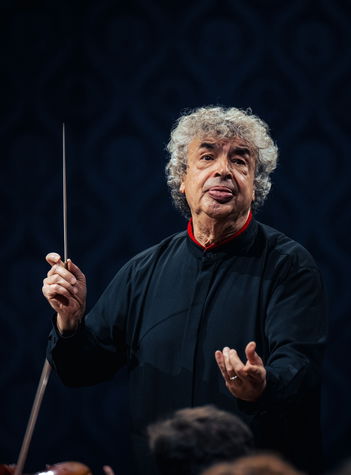

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

In Nature’s Realm, concert overture, Op. 91

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Personal relationships, friendships, and mutual respect among individuals leave a more tangible imprint on history than one might expect. An illustrative chapter of music history involved Fritz Simrock, Antonín Dvořák, Johannes Brahms, Robert and Clara Schumann, and Joseph Joachim.

Among the compositions for solo instrument and orchestra by Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904), three concertos stand out: the Piano Concerto in G minor (Op. 33), the Violin Concerto in A minor (Op. 53), and the Cello Concerto in B minor (Op. 104). The first two date from almost the same period and were both actually published in 1883, but they underwent a different genesis. While Dvořák apparently came up with the idea of composing the early version of the piano concerto in 1876 on his own, perhaps fondly imagining Karel Slavkovský at the piano, the stimulus for writing the Violin Concerto in A minor was external. The publisher Simrock commissioned the increasingly popular Czech composer to write another composition of “Slavonic” character. The Czech Suite, Op. 39, the Slavonic Rhapsodies, Op. 45, the Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, and the String Quartet in E flat major, Op. 51 were all earlier works by Dvořák that were popular items on the sheet music market and were influenced by the melodic and rhythmic patterns of the folk music of the Czechs, Moravians, and other Slavic peoples. The violin virtuoso, conductor, and director of the Hochschule für ausübende Tonkunst Joseph Joachim, whom the composer had met in early April 1879 in Berlin, also supported the idea of a new concerto. The concerto’s dedication to Joachim shows Dvořák’s regard for the chance to collaborate with the legendary violinist and pedagogue.

Dvořák began composing his violin concerto in 1879 while spending the summer in Sychrov. Two years earlier he had left his poorly paid position as the organist at the Church of Saint Adalbert in Prague’s New Town, and now he was devoting himself solely to composing. The repeated awarding of a state stipend in support of artists made it easier for him to take that step, and it also led to his friendship with Johannes Brahms, who in turn facilitated Dvořák’s contract with Simrock, which was of vital importance to him. By the end of the 1870s, Dvořák had established himself at home and abroad. However, the path to the definitive version of the violin concerto was not easy: Dvořák’s consultations with Joachim dragged on (the composer waited more than two between the spring of 1880 and the autumn of 1882 year for Joachim’s reaction), and the publisher also had conditions through his advisor Robert Keller. Paradoxically, as it turned out, Joachim, who was supposed to have been the first interpreter of the work, and who made changes in particular to the form taken by the solo part, probably never played Dvořák’s Violin Concerto in public. František Ondříček gave the premiere in October 1883, and after the successful Prague performance with the orchestra of the National Theatre, he also introduced the composition to the enthusiastic Viennese public that December with the Vienna Philharmonic and with Hans Richter on the conductor’s podium. Ondříček then continued to promote the Violin Concerto in A minor throughout his stellar career.

Dvořák went about integrating the orchestra with the solo part similarly to his great model Brahms, whose Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, dates from about the same time. Brahms also dedicated his concerto to Joachim, who premiered it in January 1879. In both cases, the strongly contoured orchestral sound is combined with a solo violin part that is technically difficult, but also richly expressive. Dvořák displays mastery of orchestration, warmth of melodic writing, and vigorous rhythm. The first movement (Allegro ma non troppo) is in an ambiguous sonata form without a recapitulation, and it is linked directly to the lyrical slow movement (Adagio ma non troppo); this smooth attacca transition was one of the points under discussion during the revisions. The Adagio is in ternary form with variations, and its mood is highlighted by the “pastoral” key of F major. The energetic third movement (Finale. Allegro giososo, ma non troppo) employs the rhythm of the furiant, a Czech folk dance, with a melancholy dumka providing contrast in the middle section.

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88