1 / 6

How is it that the Japanese understand?

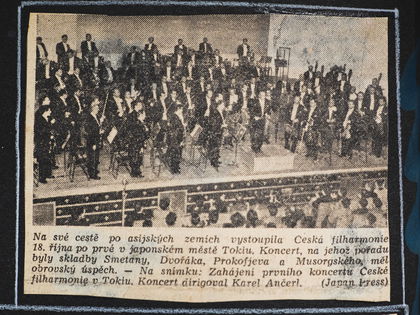

Jules Verne dreamed of a journey around the world in 80 days. Given the earth’s circumference of ca. 40,000 kilometres, the Czech Philharmonic led by Karel Ančerl actually outdistanced Phileas Fogg by more than double. On tour in 1959, the orchestra was not limited to travelling by train or ship like in the 19th century, but the journey was slowed by musical duties. In the course of 100 days, the orchestra travelled 100,000 kilometres and played nearly 60 concerts with 19 in Japan.

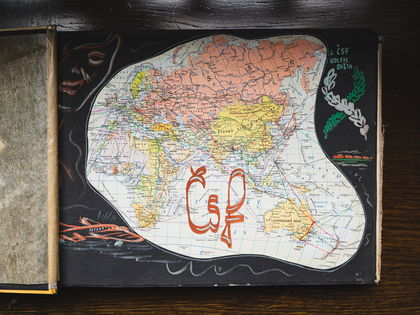

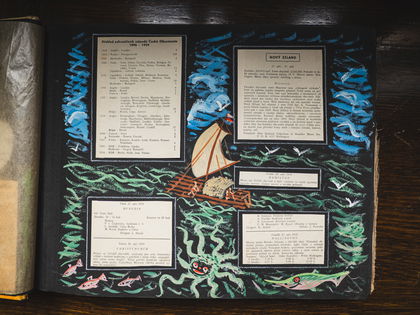

Prague, Brindisi, Damacus, Bahrain, Bombay, Rangoon, Singapore, Djakarta, Timor, Darwin, Townsville, Brisbane, Auckland. What you are reading is not a grammar school geography assignment to fill in a blank map, nor is it the plan for an adventurous expedition by explorers like Hanzelka and Zikmund. The list of 13 cities was on the sixth page of the travel itinerary received by each member of the Czech Philharmonic’s sizeable crew of musicians. The goal of the journey crossing 165 meridians was neither to conquer mountain peaks nor to hunt for lost treasures, but rather to travel as fast as possible from Prague to Auckland, New Zealand so there would be time the very next day for what was most important—giving a concert.

In 1959, the Czech Philharmonic set out on what was then not only its own biggest tour, but also the biggest tour by any symphony orchestra from any country in history. Between the afternoon of Saturday, 12 September, when the first of two planes carrying the orchestra’s musicians took off from the Prague-Ruzyně airport, and Wednesday, 16 December, when a train brought all the musicians back to Prague’s Main Station, the orchestra played for audiences in New Zealand, Australia, Japan, China, India, and the Soviet Union.

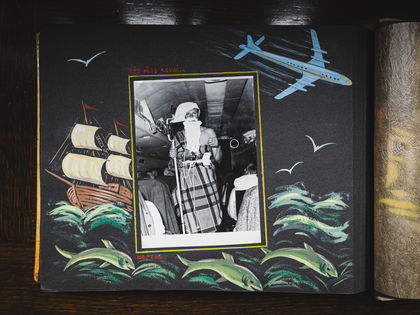

And everything went according to plan. That is, if you consider only the first 60 minutes of the three-month journey. Already during the second hour, the travellers were informed that there would be a stopover in Rome instead of Brindisi. Of course, no one minded getting to see the beauties of the Eternal City, even if only from a bird’s-eye view. There was slightly less enthusiasm over an announcement made a few hours later when the plane was taking off, or rather, trying to. Fortunately, the technical defect of the four-engine Argonaut of the airline Overseas TAAC was discovered in time, and after a tiring wait, the plane successfully lifted off from the last European runway on this expedition.

More stopovers followed, as well as dramatic changes to the climate. In Singapore, the players were rescued from a sleepless night in the heat by a mysterious piece of electrical equipment bearing a label that read air conditioning, which they encountered for the first time in their lives in the luxurious Raffles Hotel. There was no time to lose, and the ringing of alarm clocks at four o’clock a.m. was an indication that the journey had been planned by a logistics expert, and not by a musician. Before departure, everyone managed to send the first postcards back home (we would attach a photograph, but supposedly not a single one was ever delivered), and in the evening the players arrived in the southern hemisphere.

The end of the five-day journey turned into a wild race. One might have expected that the Australian captain Stevenson, who had already been entrusted with a group of the orchestra musicians in Prague, would begin to relax as he approached the end of the journey halfway around the world, wouldn’t he? Well, not quite. He suddenly got the urge to compete with the plane carrying the other half of the philharmonic crew. The second plane had left Prague two days later, but according to the flight schedule, it was supposed to reach the final destination 15 minutes earlier because the Dutch Super Constellation could fly nearly 100 km/h faster.

“So, what about the other plane? When is it supposed to arrive in Auckland?” That is what the pilot was overheard saying by the former secretary of the Prague Spring Festival Vilém Pospíšil, who squeezed on board among the orchestra players and carefully recorded his vivid impressions. Whether we call it a pilot’s pride or human vanity, the tempo to the destination had clearly been set at prestissimo. While the length of the stopover in Brisbane managed to be shortened, and despite fog at the airport in Whenuapai complicating plans for the race, Captain Stevenson managed to land in northwestern Auckland half an hour before his competitor. Now the concerts could begin.

Down Under

At the time, chief conductor Karel Ančerl recalled that “audiences were often travelling as far as six hundred kilometres.” The tour also coincided with an international rugby match—the national sport in which New Zealanders are world champions. All the more gratifying, then, was that even despite this tough competition, the opening pages of the newspapers were flooded with enthusiastic reviews and photographs of the Czechoslovak musicians.

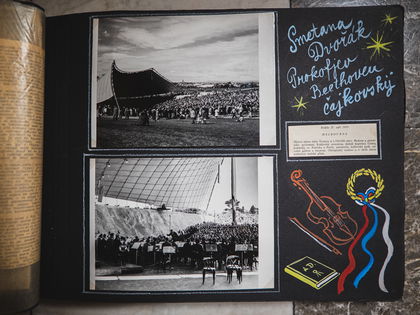

The Czech Philharmonic then became the very first foreign symphony orchestra to visit Australia. The final concert in Melbourne was scheduled for an open-air amphitheatre but was initially cancelled due to winter cold and strong winds. Yet by mid-morning, a crowd of 20,000 had gathered on site, making it clear that the concert had to go on. Despite the adverse weather, 35,000 people eventually showed up.

Of course, the journalists were interested in more than just concerts; they also asked about the players’ interests beyond music, and especially football. When they learned that among the musicians there was a capable group of players, they planned to stage a match alongside the concerts. “It never came to pass despite the great eagerness of our footballers. It was not possible to risk any potentially serious injuries at the very beginning of the concert tour. We made it up to the journalists by having our eleven finally don their jerseys and run briefly across the pitch, just so there would at least be photos”, explains Vilém Pospíšil on behalf of the Philharmonic. While throughout the entire tour the orchestra members steadfastly resisted offers to accept teaching posts, soloist engagements, or concertmaster positions, it was only in Melbourne that they received a serious offer of a football career.

Caught by a typhoon

While flying back to the northern hemisphere, the tuba player Hejda calculated that they had spent exactly 100 hours in the plane. That amounts to nearly 14 business days during the first month of the journey. Along with that, the orchestra had managed to play 23 concerts. The players agreed that on tour, they would never again be able to find any planes as slow as the Argonaut. That was a hot topic of debate for the whole crew...

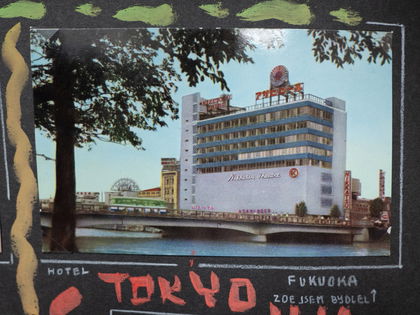

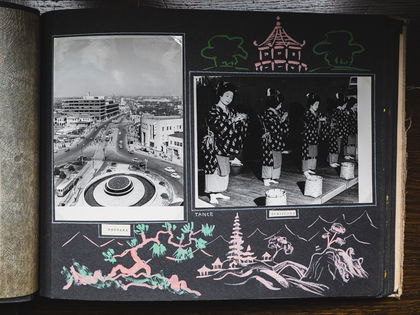

The excitement over breaking non-musical records quickly faded just before arriving in Tokyo. The plane was caught by the edge of a typhoon that had caused terrible damage in Japan not long beforehand. Fortunately, the turbulent flight and fifteen especially stressful minutes did not result in any casualties. In the end, the especially friendly local inhabitants made up for the inhospitable weather.

There were perhaps no reviews that lacked phrases like “enormous success”, “a special artistic experience”, or “an exceptional performance”. And there were plenty of reviews, but acknowledgement did not necessarily arrive only in printed form. Liquid congratulations also count. Right after the first concert, bottles of Japanese whiskey awaited the orchestral musicians on the tables with their supper.

And we can linger over dining for just a bit. After all, the sharing of meals has always been one of the experiences that bonds friendships, and especially when people are enjoying themselves at the table. Jiří Pauer, the executive director of the Czech Philharmonic at the time, recalled how “it was almost impossible to fit the legs of our trombonists, double bassists, and other tall fellows under the tiny Japanese tables!”

Jaroslav Klíma long remembered the amazing, if not downright shocking sight of “120 people struggling with short, round chopsticks… You’ve seen it in Prague, but just try eating rice with chopsticks without any practice, try keeping peas on two tiny sticks, in short—being hungry, facing a lot of food, and having nothing sturdier to get it into your mouth. And the sight of the stocky young men in white, who could astonish the local experts with the most intricate passages from Ravel, for example, meanwhile desperately chasing food around their plates—that was just as remarkable to me as the waterfalls in Nikkō or the beautiful women of the Philippines.”

Chased by Japanese Youth

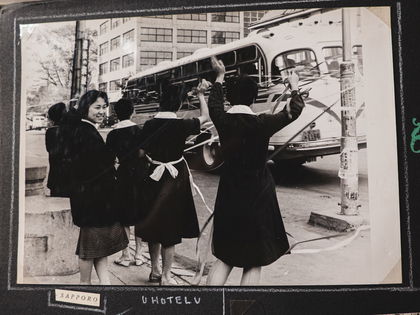

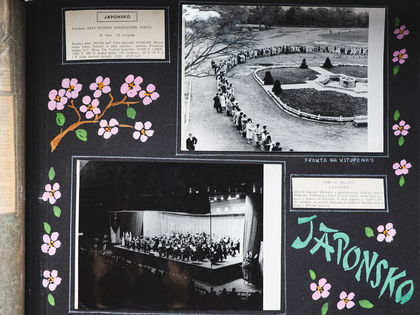

The orchestra scored not only with hosts and music critics, but also with Japanese youth. They packed concert halls with zeal, and when no music was playing, they chased the Philharmonic through the streets, seeking autographs on concert programs. The patience of fans was clear from the ticket lines stretching endlessly at every stop, but the two-kilometre queue in Sapporo is probably unbeatable.

The hotel staff were friendly as well. Farewells to the Czech Philharmonic’s bus were accompanied by ribbons, a symbol of lasting friendship. Such encouragement must certainly have been welcome to the musicians. Their journey was arduous. They often spent the night sleeping on trains, then their travels continued during the day; they only had time for a short rest before their evening concerts.

To hear the Czechoslovak musicians, the Japanese music lovers did not necessarily have to travel to the capital city. In the course of four weeks, the orchestra toured the whole country from Sapporo in the northeast to the central Japanese cities Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka, Kyoto, Okayama, and Hiroshima, then on to Fukuoka and Nagasaki in the southwest. They ended the month-long tour with two concerts at a sports arena in Tokyo, where 12,000 audience members came each time to bid them farewell. Since then, the Czech Philharmonic has returned to Japan 27 times, giving 373 concerts there.

We are grateful that Vilém Pospíšil recorded these vivid memories in the book S Českou filharmonií třemi světadíly (With the Czech Philharmonic on Three Continents). You can certainly still find it somewhere on the shelves of antiquarian bookshops. And if you are wondering what the journey down under looked like from the perspective of the competing aircraft, read the book Dálky (Distances) by Jaroslav Putík.

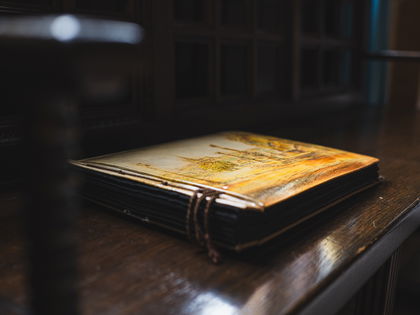

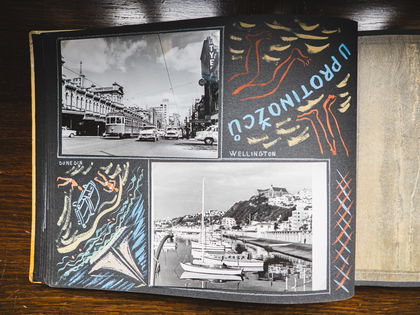

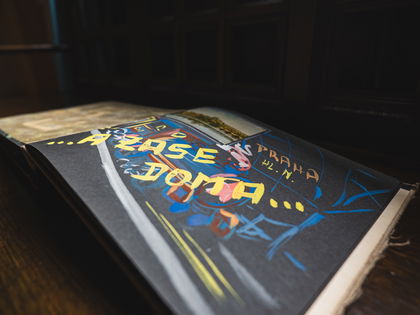

This fantastic album featuring photographs, sketches, and clippings of reviews, letters, and newspaper articles was created by Mr. Slavík, former trombonist of the Czech Philharmonic and participant in the 1959 tour. A debt of thanks is also owed to the current trombone players who felt it would be a shame for the album to remain unused in Mr. Slavík’s locker. We wholeheartedly agree and are grateful that at the end of last season they donated it to the Czech Philharmonic archive.

Browse through the album

Join 20 000+ readers

Receive news from the Czech Philharmonic, including exclusive magazine content as well as news from Prague’s Rudolfinum every two weeks.