Performers

Seong-Jin Cho piano

With an innate musicality and overwhelming talent, Seong-Jin Cho has established himself worldwide as one of the leading pianists of his generation and most distinctive artists on the current music scene. His thoughtful and poetic, assertive and tender, virtuosic and colourful playing can combine panache with purity and is driven by an impressive natural sense of balance.

Seong-Jin Cho was brought to the world’s attention in 2015 when he won First Prize at the Chopin International Competition in Warsaw, and his career has rapidly ascended since. In January 2016, he signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon. An artist high in demand, Cho works with the world's most prestigious orchestras including Berliner Philharmoniker, Wiener Philharmoniker, London Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre de Paris, New York Philharmonic and The Philadelphia Orchestra. Conductors he regularly collaborates with include Myung-Whun Chung, Gustavo Dudamel, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Andris Nelsons, Gianandrea Noseda, Sir Simon Rattle, Santtu Matias Rouvali and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

An active recitalist very much in demand, Seong-Jin Cho performs in many of the world’s most prestigious concert halls. During the coming season he is engaged to perform solo recitals at the likes of Carnegie Hall, Boston Celebrity Series, Walt Disney Hall, Alte Oper Frankfurt, Liederhalle Stuttgart, at Laeiszhalle Hamburg, Berliner Philharmonie, Musikverein Wien and he debuts in recital at the Barbican London.

Seong-Jin Cho’s recordings have garnered impressive critical acclaim worldwide. The most recent one is of Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and Scherzi with the London Symphony Orchestra and Gianandrea Noseda, having previously recorded Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 as well as the Four Ballades with the same orchestra and conductor. His latest solo album titled The Wanderer was released in May 2020.

Born in 1994 in Seoul, Seong-Jin Cho started learning the piano at the age of six and gave his first public recital aged 11. In 2009, he became the youngest-ever winner of Japan’s Hamamatsu International Piano Competition. In 2011, he won Third Prize at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the age of 17. From 2012–2015 he studied with Michel Béroff at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris. Seong-Jin Cho is now based in Berlin.

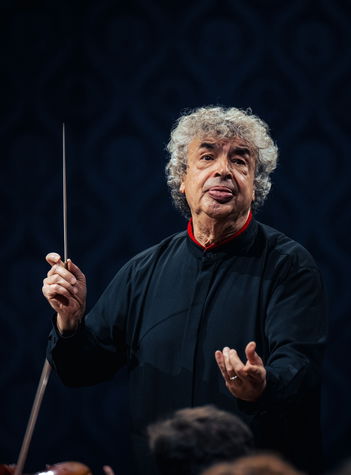

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Maurice Ravel

Piano Concerto in G major

Maurice Ravel did not leave behind a large musical legacy. Some biographers claim this was because of the composer’s other activities—he was also working as a concert pianist, a conductor, and a teacher. Others say it was his meticulousness and the exacting standards he set for himself. He wrote a number of individual compositions and cycles of pieces for his own instrument, the piano, including music for solo piano, for piano four-hands, and for two pianos. He also wrote two piano concertos, both during his late creative period, composing them simultaneously between 1929 and 1931. The Piano Concerto in D major for the left hand was written on commission for the one-handed pianist Paul Wittgenstein (1887–1961), who had also asked other composers of his day to write works for his repertoire.

In his Piano Concerto in G major, Ravel employed a variety of stylistic resources ranging from Spanish folk elements to the jazz influences of his day. He conceived the orchestral accompaniment in an original manner, giving various instruments room to play solo passages. The two outer movements contrast effectively with the melancholy central Adagio. The first movement in sonata form surprisingly repeats material from the development section after the recapitulation and cadenza. The slow movement opens with a long piano solo, with wind instruments taking up the theme one after another. The theme itself has been compared to that of the slow movement of Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet. The winds also play a major role in the orchestration of the rondo finale.

Ravel expected that, as with other works he had written, he would himself be the concerto’s first performer: “It was an interesting experience to work on both concertos at the same time. The one I will be playing myself is a concerto in the true sense of the word. What I mean is that it is written in the spirit of Mozart and Saint-Saëns. In my opinion, the music of a solo concerto has to be light and brilliant, and it should not strive for depth or for dramatic effects”, he wrote. However, problems with Ravel’s health prevented him from playing the piano part. The concerto was premiered on 14 January 1932 with Marguerite Long as the soloist and with Ravel leading the orchestra. The two artists then embarked on a four-month tour, during which they also played the new concerto on 18 February 1932 at a philharmonic concert of the New German Theatre in Prague: “A delicately crafted, polished composition full of spirit, taste, and precision, and a work of art clear as crystal, elegant, and lively”, wrote a Prague critic. “The piano part allows for both mechanistic playing and Lisztian virtuosity, though musicality is required above all in the difficult harmonic passages.” The audience even insisted that the final movement be repeated.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Op. 65

During the Second World War, Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975) composed three symphonies. He wrote his Ninth in 1945, between the war’s end in Europe and its conclusion in the Pacific. At the premiere on 3 November, Stalin had expected a grandiose work with chorus and vocal soloists, but instead Shostakovich presented a symphony that was shorter than the first movement of either of its two predecessors, that was optimistic, and that formally and sonically resembled the classical symphonies of Mozart. It is not as intellectually weighty as its two predecessors, nor is it by any means as monumental as the famous “Ninths” by Beethoven or Mahler. The composer said he started thinking about the Seventh before the war had begun, but most of it was written in the last months of 1941. In September, German troops besieged Leningrad, and Shostakovich’s native city and its inhabitants remained under a cruel and devastating blockade for 872 days. That October, Shostakovich and his family were evacuated to Kuybyshev (now Samara), he finished the symphony in December, and it was premiered in early March. A few months later, on 9 August 1942, the Seventh was also heard in Leningrad itself under dramatic circumstances thanks to the enormous personal efforts of everyone involved. The work quickly got the name Leningrad Symphony and became a symbol of Russia’s indomitable spirit, determination, and resistance to Nazism.

Shostakovich escaped the horrifying conditions in besieged Leningrad, but the war itself remained present in his life. Immediately after the June invasion, he volunteered repeatedly to join the army, but the officials and commissars turned him down each time so he could devote himself to his civilian vocation, so he gave concerts, composed, and taught at the conservatoire, where he patrolled the roof as a volunteer fireman. After finishing his Seventh Symphony, he said he wanted to begin composing an oratorio about the heroic defenders of Moscow, an opera, and a ballet. In the end, however, he channelled his energies into work on another symphony written during the summer of 1943, which he spent in the city Ivanovo north of Moscow. “In recent days, I finished work on my new Eighth Symphony. I wrote it rather quickly, in a bit over two months. […] It lacks any kind of narrative. It just reflects my thoughts and experiences and my reactions to joyous news about victories of the Red Army. This new work of mine is a peculiar attempt to gaze into the future, into the post-war era”, Shostakovich wrote on 18 September for the weekly journal Literature and the Arts.

That February, the Soviet army had been victorious at Stalingrad, and as a Soviet composer he was expected to write a symphony that was celebratory and heroic. Notwithstanding the composer’s public proclamations, his Eighth is nothing of the kind. Against the backdrop of great battlefield victories, Shostakovich saw not triumph, but millions of ruined lives, despair, and the futility of a war that was corroding both society and the individual from within. During the Great Terror of the 1930s, Stalin had many of Shostakovich’s friends executed, and the composer spent nearly his whole life in fear that he would meet a similar fate. Having become popular in the West as well, especially after the success of the Leningrad Symphony, Shostakovich sometimes enjoyed the protection of the regime, but at other times he suffered criticism, threats, and humiliation. He therefore became a master of irony. He said one thing while thinking something else, but it was through his music that he could be the most sincere. That is what the Eighth Symphony is like: here ironic, there sincere, and at times even absurd, just as war and living in wartime seemed absurd to Shostakovich.

Shostakovich characterised his Eighth as a work full of dramatic internal conflicts. This applies both to its philosophical meaning and to the music itself. The first movement is characteristic in this regard, beginning at a slow tempo and in a gloomy mood, alternating in places with lyrical episodes for the woodwinds. One of the longest movements in any of Shostakovich’s symphonies, it reaches its climax around its midpoint, when a gradual crescendo arrives at a powerful forte Allegro. The seemingly chaotic sound of the roaring orchestra is put into order by a strong but irregular march rhythm. The first movement ends slowly and quietly, but the music’s character remains more threatening than conciliatory. The threat becomes reality in the second, third, and fourth movements. Each is a march in its own way—the second with ironic elements in a dance-like scherzo, and the fourth like a dark, sluggish funeral march. A certain calming and catharsis finally arrives with the concluding Allegretto in the form of lyrical melodic passages and pastoral motifs, but here, too, there is no lack of dramatic episodes, and even the lyrical-sounding conclusion in C major is haunted by dark echoes in the contrabass. “I can express the philosophical idea of my new work very briefly in just three words: life is beautiful. All that is evil and ugly will disappear, and beauty will triumph”, Shostakovich wrote in Literature and the Arts. It is up to everyone who listens to the Eighth Symphony to judge how ironically or sincerely those words were meant.