The concert is being organized in cooperation with the Lunchmeat festival.

![]()

The programme is based on a musical part but also on a spoken word that will be given in Czech language only. The programme will not be supplied with English subtitles.

Performers

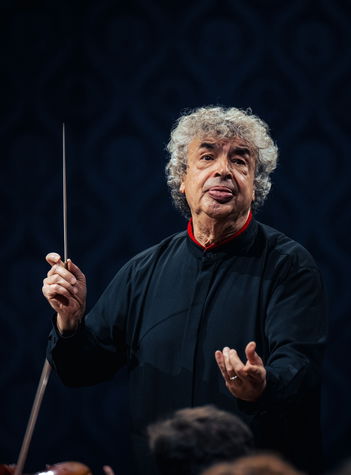

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Czech Philharmonic

Chosen as Gramophone’s 2024 ‘Orchestra of the Year’, this season the Czech Philharmonic will be a guest in the most prestigious halls across East Asia – Taiwan, Japan and South Korea – as well as major cities in Germany, Italy, Austria, Luxembourg, Belgium, Sweden and Finland. In the Czech Republic, the orchestra appears at its home, the Rudolfinum in Prague, at festivals including Prague Spring, Dvořák Prague and Smetana Litomyšl, as well as at international festivals such as Grafenegg, George Enescu and Bad Kissingen. Following in the footsteps of Yuja Wang, Magdalena Kožená, Sir András Schiff and Daniil Trifonov, Evgeny Kissin will be the Czech Philharmonic’s 130th season Artist-in-Residence.

Alongside its celebrations of Shostakovich’s 50th anniversary, Ravel’s 150th anniversary and the 150th anniversary of Vltava – the iconic second poem of Má vlast – the Czech Philharmonic will shine a spotlight on contemporary music this season with the appointment of its first ever Composer-in-Residence, Bryce Dessner. The European and Czech premieres of two new works by Dessner will be led by Chief Conductor and Music Director Semyon Bychkov and Principal Guest Conductor Jakub Hrůša. Further national premieres by John Adams, Luigi Dallapiccola, György Kurtág, Witold Lutosławski, Guillaume Connesson and Wynton Marsalis will be conducted by Principal Guest Conductor Sir Simon Rattle, Sir Anthony Pappano, Thomas Adès, Stéphane Denève and Cristian Mǎcelaru. Pappano will return in summer 2026 with the London Symphony Orchestra to perform in Prague as part of a new Czech Philharmonic initiative.

The Czech Philharmonic’s extraordinary and proud history reflects both its location at the heart of Europe and the Czech Republic’s turbulent political history, for which Smetana’s Má vlast (My Country) has become a potent symbol. For the 2024 Year of Czech Music and the 200th anniversary of Smetana’s birth, the orchestra released a new recording of the work with Semyon Bychkov – which won the 2025 BBC Music Magazine Orchestral Award – and together they presented a three-day residency at Carnegie Hall as part of Czech Week in New York.

Throughout the orchestra’s history, two features have remained at its core: its championing of Czech composers and its belief in music’s power to change lives. Alongside the Czech Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, Orchestral Academy, and Jiří Bělohlávek Prize for young musicians, a comprehensive education strategy engages with more than 400 schools and an inspirational music and song programme led by singer Ida Kelarová for the extensive Romany communities, has helped many socially excluded families to find a voice. The Czech Philharmonic additionally runs an annual educational exchange programme with London’s Royal Academy of Music.

An early champion of the music of Martinů and Janáček, the Czech Philharmonic’s first concert in 1896 was an all-Dvořák programme conducted by the composer himself. The orchestra is known for its definitive interpretations of Czech composers, as well as a special relationship with the music of Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Mahler. The Czech Philharmonic’s first complete, new recording of Mahler’s symphonies for more than 40 years ago will be released by PENTATONE in spring 2026 conducted by Semyon Bychkov.

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”

Dvořák’s prestigious invitation to New York did not come out of nowhere. For years, his music had already been familiar in the United States, and American newspapers had been writing about his successes in Europe as a composer and conductor. Above all, however, for America Dvořák was iconic as a national composer. “Americans expect great things from me, and above all, supposedly, that I will show them the way to the promised land and to the realm of new, independent art, in short, how to create the music of a nation!! […] Certainly, this is an equally great and beautiful task for me, and I hope I shall have the good fortune to succeed with God’s help. There is more than enough material here,” wrote the composer to his friend Josef Hlávek after arriving in America. Dvořák did, in fact, delve into America’s musical material with great interest, as is revealed in an interview for the New York Herald: “Since I have been in this country I have been deeply interested in the national music of the negroes and the Indians. […] I intend to do all in my power to call attention to this splendid treasure of melody which you have.” Dvořák did not borrow the melodies, however. He created his own melodies using many of the characteristic features of folk songs that he combined with the essence of American folklore. In addition, the motifs from the new Symphony in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”, did not come into the world instantly in the form in which we now know them. This is documented by the composer’s sketches, in which the now famous themes appear still with many deviations from the final version. It is clear that during the compositional process, Dvořák was giving ever deeper expression to the “American spirit” that he wanted the music to embody, adding syncopations including a special rhythm known as the “Scotch snap”, highlighting the pentatonic scale etc. However, his new symphony was by no means an attempt to do everything differently from his previous symphonies. As he was finishing the score, he brought this up in a letter to his friend Göbl: “I’m just now finishing my Symphony in E minor, which will be strikingly different from my earlier ones, mostly in terms of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic figures—just my orchestration has not changed, something in which I probably will not advance any further, nor do I wish to, and I have my reasons.”

The composer also mentioned the work’s tempestuous reception at the premiere at New York’s Carnegie Hall in December 1893 (Anton Seidl conducted the New York Philharmonic) in a letter to his publisher Fritz Simrock in Berlin: “The symphony’s success on December 15th and 16th was magnificent; the newspapers say that no composer has ever before achieved such a triumph. I was seated in a box, the hall was occupied by New York’s most elite public, and the people applauded so much that I had to wave from my box like a king to show my gratitude! Like Mascagni in Vienna (don’t laugh!). You know that I prefer to try to avoid such ovations, but I had to do this and show myself.” The composer did not inscribe the title “From the New World” on the score’s title page until a few months after finishing the work; it was on the very day that he handed the score over to the conductor for rehearsals. The title of the first work he had written in America gave rise to a great deal of comment in newspaper articles. Having read them, the composer supposedly remarked with a smile: “Well, it seems I have confused their minds a bit.”

Předehra k opeře Prodaná nevěsta

Moderní opera, která je zároveň plně česká. Takový cíl si stanovil Bedřich Smetana poté, co si ve Výmaru na podzim roku 1857 vyslechl pichlavou poznámku vídeňského dirigenta Johanna von Herbecka, že Češi jsou sice výteční interpreti, ale nedokážou vytvořit vlastní hudbu. Smetany se tento výrok nepříjemně dotkl a byl odhodlán dokázat, o jak mylný názor se jedná: „Přísahal jsem tam a tehdy, že právě já bych měl zplodit českou národní hudbu.“ Svému slibu, jak už dnes víme, dostál, nestalo se to však hned. Existenční důvody vedly skladatele ještě na nějaký čas zpět do Göteborgu, kde pracoval jako ředitel Filharmonické společnosti. Teprve pozitivní zprávy o změnách v pražském kulturním životě a naděje na založení samostatného českého divadla rozhodly o Smetanově návratu do Čech na jaře roku 1861. Jeho prvním příspěvkem k vytvoření české národní opery se stalo komplikované historické drama Braniboři v Čechách, při jehož dokončování už skicoval jednu z nejčeštějších českých oper, již později nazval Prodaná nevěsta. Pracoval na ní pomalu, uvážlivě a pečlivě, po premiéře na jaře roku 1866 ji několikrát revidoval, dokud nezískala podobu, s níž by byl plně spokojen. Zcela netypicky vznikla jako první z celé opery svižná energická předehra (Vivacissimo) s rozsáhlým smyčcovým fugatem, jež výtečně navozuje pozitivní atmosféru celého díla. Konečná verze půvabně komické Prodané nevěsty zazněla poprvé v září roku 1870 v Prozatímním divadle v Praze, světového ohlasu se dočkala až v roce 1892 zásluhou úspěšného hostování pražského Národního divadla na Mezinárodní hudební a divadelní výstavě ve Vídni. Svou londýnskou premiéru měla o tři roky později.

Bedřich Smetana

My Country, cycle of symphonic poems

By the time that Smetana was in Sweden in the 1850s, he had begun to take interest in a recent musical discovery known as the symphonic poem, invented by Smetana’s mentor, the composer Franz Liszt. The symphonic poem was intended as an emphatic response to all the criticism aimed at music as an artform: according to many aestheticians, the great weakness of music was its abstractness. For this reason, composers began writing works with a concrete extramusical programme such as, for example, a story, event, or description of nature. While working in Sweden from 1856 to 1861, Smetana wrote three symphonic poems: Richard III, Hakon Jarl, and Wallenstein’s Camp. Then in he wrote respectfully to Liszt: “Consider me to be the most fervent supporter of our artistic movement, who stands for its holy truth by word and deed.”

It was not until he was back in Bohemia over a decade later that her returned to thinking about more symphonic poems. He created the extraordinary musical cycle Má vlast (My Country), a unique concept in all of music history worldwide, from 1874 to 1879. By that time, he was totally deaf. He used music to portray the myths and history of Bohemia, the country where he lived, and also his vision of the “resurrection of the Czech nation”, which was then one of the nations of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. For this very reason, Smetana’s Má vlast enjoys a unique standing in the Czech musical tradition.

The creation of any more symphonic poems by Smetana is not mentioned until 1872. In November, the music journal Hudební listy reported that Bedřich Smetana “having fully completed his great patriotic opera Libuše (…) is now moving on to larger-scale orchestral compositions titled Vyšehrad and The Moldau.” By all accounts, Smetana did not plan the whole cycle in advance; instead, it took shape over several years. In 1873, the journal Dalibor published a somewhat fanciful article, claiming that Smetana was composing “a whole cycle of symphonic poems with the overall title The Homeland and with individual sections titled Říp – Vyšehrad – The Moldau – Lipany – White Mountain etc.”, but the story was not all that far from the truth when it claimed that the composer was creating a work “based on our country’s most important moments of glory and misfortune.”

As “programme music”, Má vlast has meaning that goes beyond the world of notes, chords, or melodic lines; it involves people, things, places, and stories of the past and present. Smetana succeeded at capturing what one might call the “Czech soul” in a remarkably comprehensive way, and in Má vlast he created an amazingly timeless composition. All the political slogans of the latter half of the 19th century, when the work was written, have since inevitably become outdated (as do all political slogans ultimately), but Smetana’s music still finds a way to reach, awaken, and inspire listeners.

Smetana’s Má vlast is associated with the history of the Czech Philharmonic like few other works. It is part of a great performance tradition that dates back to 1901, when the orchestra first performed the whole cycle of symphonic poems. Since then, the Czech Philharmonic has played the work over 700 times! No other orchestra in the world has played Má vlast so often. It has given performances on workdays, weekends, and holidays, and there have even been a number of commemorative performances when Smetana’s music had a very special resonance.

1924 saw the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Smetana’s birth, and for the occasion Václav Talich prepared a performance of Má vlast with the combined orchestras of the Czech Philharmonic and the Prague Conservatoire. Má vlast was also the first work recorded by the Czech Philharmonic with Talich on the His Master’s Voice label. Smetana’s cycle became symbolically important during the Nazi occupation and the Second World War. An incredible recording was made of Talich’s Má vlast performance in June 1939, and hearing it still sends a chill up one’s spine. They play as if their lives depended on it, and at the end, the audience sang the Czech national anthem Kde domov můj (Where My Home Is). At such times, music ceases to be a kind of cultural experience that we come to enjoy, but instead sears its way into our innermost being.

For Czech listeners, in difficult times Má vlast sounds urgent like a call to arms, but there are also moments of liberation when Smetana’s special music affirms that “the governance of your own affairs will return to you, O ye Czech people”. That is how it was in June 1945, when the Czech Philharmonic played Smetana’s cycle on Old Town Square to express thanks for the end of the war. That is how it was in May 1968, when Karel Ančerl and the orchestra opened the Prague Spring Music Festival in an atmosphere of great societal revival and liberalisation after 20 years of totalitarianism. And that was again the case in the spring of 1990, shortly after the communist regime had definitively fallen. After 42 long years of exile, the conductor Rafael Kubelík returned home. “I have fervently awaited this moment, and I believed that it would come one day. I am grateful to God, to the whole nation, to my friends, and to all of you.” Those were Kubelík’s first words upon returning to his homeland on 8 April 1990. “What Václav Havel has been able to achieve recently is not a miracle, but rather proof that there are no miracles and that in mankind there is strength that can truly move mountains.”

For nearly the entire 20th century, Smetana’s cycle was something like the exclusive property of the Czech Philharmonic and other Czech orchestras. Today those orchestras face competition over which one can only rejoice. Má vlast is a valued item in the repertoire of the Berlin Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic, and the orchestras in Munich, Bamberg, Cologne, Hamburg, Madrid, Amsterdam, and Cleveland. It was heard recently at the Prague Spring Festival and at the 2022 Salzburg Festival played by Barenboim’s West-Eastern Divan Orchestra consisting of young musicians from the Middle East. Má vlast has become an international work.