1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Simon Rattle

Hector Berlioz’s second symphonic work takes us to Italy. Accompanying us will be Lord Byron’s romantic hero Harold, whose voice will be Amihai Grosz, the principal violist of the Berlin Philharmonic. Upon returning from the musical universe of Witold Lutosławski, we will hear Beethoven’s majestic Eroica, originally dedicated by the composer to Napoleon.

Programme

Hector Berlioz

Harold in Italy, symphony with solo viola, Op. 16 (43')

— Intermission —

Witold Lutosławski

Chain III (Czech premiere) (10')

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. in 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica” (50')

Performers

Amihai Grosz viola

Czech Philharmonic Youth Orchestra*

Simon Rattle conductor

Czech Philharmonic

* The Czech Philharmonic Youth Orchestra is playing Berlioz’s symphony Harold in Italy.

Customer Service of Czech Philharmonic

Tel.: +420 227 059 227

E-mail: info@czechphilharmonic.cz

Customer service is available on weekdays from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. Whenever you need to purchase a wheelchair-accessible ticket.

“Beethoven is dead, and Berlioz alone can revive him.”

– Nicolò Paganini, letter to Hector Berlioz dated 18 Dec. 1838

In 1830, Berlioz completed his Symphonie Fantastique, and he did not intend to write another symphonic work. He kept his word for three years until he got a commission from the virtuoso Nicolo Paganini. Shortly beforehand, the violinist had acquired a viola made by Antonio Stradivari, and he was looking for a composition to play on it.

When searching for a suitable subject, Berlioz considered a work with choir about the last moments of the life of Mary, Queen of Scots, but in the end an orchestral composition with viola solo won out. The work also reflected recollections of Berlioz’s earlier, rather unproductive stay in Italy as a winner of the Prix de Rome, a French stipend for gifted artists.

“It occurred to me to write a series of scenes for orchestra with solo viola involved as a more-or-less active character who always retains his own individuality. By placing it among poetic memories formed from my wanderings in the Abruzzi, I wanted to make the viola a kind of melancholy dreamer in the manner of Byron’s Childe-Harold. Thence the title: Harold in Italy.”

Paganini admired Berlioz, but the commissioned composition did not seem virtuosic enough for the presentation of a rare instrument, and he refused to play it. Four years later, however, when he attended the premiere in Paris at a concert conducted by Berlioz, he changed his opinion. He compared the composer to Beethoven and wrote him a bank draft for 20,000 francs, thanks to which Berlioz was able to compose a third symphony.

On the second half of the concert, we will hear Beethoven’s Third Symphony. “Beethoven, scornful and brutal, and yet gifted with deep sensitivity. It seems I would forgive him everything, his scorn and his brutality,” said Berlioz in deep admiration of his colleague’s work. The link between the two composers in the middle of the programme is Chain III by Witold Lutosławski.

Performers

Amihai Grosz viola

Simon Rattle conductor

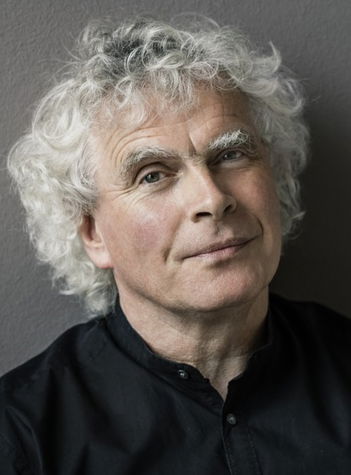

We have seen one of today’s most distinguished conductors, Sir Simon Rattle, relatively often at the Rudolfinum in recent years. His long-term cooperation with the Czech Philharmonic has led to his appointment together with his wife, mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená, as Artist-in-Residence for the 2022/2023 season. At his appearances with the Czech Philharmonic, he has performed a number of symphonic works and, most notably, compositions for voices and orchestra from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the repertoire for which Rattle has been the most acclaimed. He appeared most recently at the Rudolfinum in February 2024 with the pianist Yuja Wang, with whom he made a Grammy-nominated recording from their joint tour of Asia in 2017. From the 2024/2025 season, he becomes the Principal Guest Conductor of the Czech Philharmonic.

A native of Liverpool and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Music has held a series of important positions in the course of his long career. He came to worldwide attention as the chief conductor of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, where he was employed for a full 18 years (for eight years as its music director); next came 16 years with the Berlin Philharmonic (2002–2018; artistic director and chief conductor) and six years with the London Symphony Orchestra. He opened the 2023/2024 season as chief conductor of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. He also leads the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment with the title of “principle artist”, and he is the founder of the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group. Besides holding full-time conducting posts, he maintains ties with the world’s leading orchestras and gives concerts frequently in Europe, the USA, and Asia.

He has made more than 70 recordings for EMI (now Warner Classics). He has won a number of prestigious international awards for his recordings including three Grammy Awards for Mahler’s Symphony No. 10, Brahms’s German Requiem, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which he recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Besides the prizes mentioned above, Rattle’s long-term partnership with the Berlin Philharmonic also led to the new educational programme Zukunft@Bphil, which has achieved great success. Even after moving on from that orchestra, Rattle did not abandon his engagement with music education, and he has taken part together with the London Symphony Orchestra in the creation of the LSO East London Academy. Since 2019, that organisation has been seeking out talented young musicians, developing their potential free of charge regardless of their origins and financial situation.

Compositions

Hector Berlioz

Harold in Italy, symphony with solo viola, Op. 16

The French composer Hector Berlioz (1803–1869) described the gestation of Harold en Italie, symphony with viola solo, in his Mémoires. He recounted how in December 1833, following a concert featuring his works, including Symphonie fantastique, he noticed “in the middle of the hall a man with long hair and piercing eyes, with a strange, haggard face, a creature haunted by genius, a Titan among giants, a man whom I had never seen before, the first sight of whom stirred me deeply. He stopped me when I passed by to shake my hand, and lavished glowing praise upon me [...]; it was Paganini...“ A few days later, the legendary violinist, and also brilliant violist and guitarist, visited Berlioz at his Paris apartment and commissioned a concerto for viola. Berlioz was wary, objecting that he himself did not play the viola and thus could not comply with Paganini’s request. Yet Paganini was adamant. “In order to oblige the celebrated virtuoso, I attempted to write a solo for viola, but one that would involve the orchestra in such a manner as to not anyhow reduce the contribution of the other instruments. I was convinced that Paganini’s powerful and captivating execution would ensure that the viola had all its due prominence,” Berlioz wrote. The press soon learned about Paganini’s commission from Berlioz, and announced a huge piece named Les dernier instants de Mary Stuart (“The Last Moments of Mary Stuart”), bearing the secondary title “dramatic fantasy for orchestra, chorus and solo viola”, yet there is no other proof confirming this claim. Furthermore, Berlioz recalled that hardly had he completed the sketch of the first movement when Paganini wanted to see the work. “Upon having counted the rests, he exclaimed: It won’t do! I am silent for too long!’’ The two artists then failed to reach agreement, and parted. Berlioz intended to write a series of orchestral scenes, in which the viola would represent a person, yet not Mary Stuart. His idea was to reflect in the piece Lord George Gordon Byron’s epic poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and the impressions from his recent wanderings in the Abruzzi Apennines, with the central character being a “melancholy dreamer after the fashion of Byron’s Harold”. In so doing, Berlioz would repeat the notion he had applied in the Symphonie fantastique: the viola’s opening theme echoes throughout the piece, while other melodies join in as travel companions. The first movement, “Harold aux montagnes”, presents scenes of “happiness and joy”; the second, “Marche des pèlerins”, resounds with the pilgrims’ singing evening prayer; the third, “Sérénade”, depicts an “Abruzzian mountain dweller singing to his beloved”. The fourth movement, “Orgie de brigands”, renders an “orgy of the brigands”, yet also recalls the earlier scenes. In a letter written six years after Harold en Italie’s first performance, Berlioz defined the final movement as “a furious orgy where wine, blood, joy, rage, all combined, display their intoxication. The rhythm now hobbles, now rushes forth, the lips seem to vomit curses and to answer prayers with blasphemies; they laugh, drink, fight, destroy, slay, violate and run riot, while the viola, Harold the dreamer, flees in horror to hear the quivering tones of an evening song in the distance.” Some of the later commentators, who had not been aware of Berlioz’s description, conjectured that Harold dies amid the brigands, but, all the tumultuous action notwithstanding, the composer did not go that far. Noteworthy is how akin in content the fourth movement of Harold en Italie is to “Marche au supplice” (The March to the Scaffold), the fourth movement of the Symphonie fantastique, as well as the “Chanson de brigands” (“Brigandsʼ Song”) in its “sequel” Lélio, and the fact that the previous scenes are recollected in the form of quotations from all the preceding movements. Just like the other two works, Harold en Italie harbours autobiographic traits, with Berlioz identifying with Byron’s hero.

Harold en Italie was premiered on 23 November 1834 in Paris by the Orchestre de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire and the soloist Christian Urhan (1790–1845), a violinist, violist, organist and composer, under Narcisse Girard, conductor of the Grand Opéra. In his Mémoires, Berlioz wrote that the audience demanded that the second movement, “Marche au supplice”, be repeated. It is a truly impressive piece of music, in which Berlioz brought to bear his supreme instrumentation skills, combining bells, harp and woodwinds, yet Girard, evidently somewhat unsettled by the audience response, ruined the encore. Consequently, in the days that followed Berlioz faced – not for the first time – mockery on the part of the critics and in anonymous letters alike. Yet he would ultimately gain the coveted recognition. On 16 December 1838, four years after its premiere, a concert including Harold en Italie was attended by Paganini, who was so enthralled by the work that after the performance he dragged Berlioz on to the stage and knelt before him. Two days later, the feted musician sent the composer a congratulatory letter, enclosing a bank draft for an enormous sum. Yet Paganini would never perform the piece himself. With Harold en Italie, Berlioz broke the convention of virtuoso concertos, showcasing as it did technical brilliance, and set out on the path towards the symphonisation of the form, which other composers followed.

Witold Lutosławski

Chain III

The Polish composer Witold Lutosławski (1913–1994) studied mathematics, natural sciences, music theory, the violin and the piano. He ultimately opted for music. His artistic career was, however, suspended by the outbreak of WWII, during which he, along with Andrzej Panufnik, earned a living in bars and cafes as a piano duo. After the war, he began working at the radio, and also wrote incidental and dance music. In 1947, Lutosławski completed his Symphony No. 1, which he had started to write in 1941. In the early 1960s, he gained international renown as an avant-garde composer, primarily after works of his had been performed at the Warszawska Jesień (Warsaw Autumn) festival of contemporary music. In the mid-1970s, Lutosławski began applying his own formal approach, based on the interconnection of musical ideas, which would become quintessential for his creation. “Over the past few years, I have worked on a new musical form, linking together two independent layers. Sections within these layers start and end at different times,” Lutosławski said. These interlocking themes give rise to a “chain”. (Named after this principle is the annual Chain Witold Lutosławski Festival, whose 22nd edition was held in Warsaw this year.)

Between 1983 and 1986, Lutoslawski conceived Chain I, for 14 instruments; Chain II, subtitled Dialogue for Violin and Orchestra; and Chain III, for orchestra. The latter was commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, who premiered it on 10 December 1986, with the composer conducting. The piece received its first performance in Europe in October 1987 in London. Chain III consists of three parts. Each of the 12 ideas of the first section is presented by a group of instruments, overlapping with another group made up of different instruments, with the links in the chain intersecting further on, building up a momentum culminating in a passage for winds. The chaining in the second part is dominated by a melody in the violin, with all the instruments joining together and ultimately reaching a collective climax. In the final part the preceding energy appears to have ebbed away, with the music seemingly leading to a conventional symphonic ending, yet the final cadenza is cut off by jarring chords.

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 3 in E Flat Major, Op. 55 (“Eroica”)

The history of Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55, by Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) has been subject to extensive research, with biographers’ reflections about its context and significance surpassing the framework of the music itself. Scholars have explored Beethoven’s motives leading to writing the symphony, speculated about the composer’s worldview and formulated his political beliefs, while numerous hypotheses pertain to the piece’s title and dedication. According to some sources, Beethoven was encouraged to create the symphony by General Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, French ambassador to Austria, whom he admired and whose salon in Vienna he would often visit. The second movement, “Marcia funebre”, has been associated with the death of Admiral Horatio Nelson (who, however, died at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, a year after Beethoven had completed his second symphony), while others have linked it with the composers’ penchant for Ancient heroes. The first sketches of the work date from 1802, when Napoleon Bonaparte was proclaimed First Consul for Life of the French Republic. Beethoven worshipped Napoleon and everything French to such a degree that he even considered moving to Paris. He originally dedicated his Symphony No. 3 to Napoleon Bonaparte, yet had to change his mind, as his intention met with disapproval on the part of his patron, the Prince of Lobkowitz, who threatened not to pay a generous fee and also extorted the exclusive performance rights for half a year. Beethoven resolved the matter through compromise, dedicating the symphony to Lobkowicz, yet titling it “Bonaparte”. Nevertheless, when, in the middle of May 1804, Napoleon declared himself Emperor of the French, Beethoven, according to his secretary Ferdinand Ries, flew into a rage and duly tore the title page of the score into pieces. The original autograph has not survived, but the change of name is also attested to by a copy of the first page, on which the original title was removed so vehemently that the paper was torn. In late May and early June 1804, the first rehearsals took place in private at the Palais Lobkowitz in Vienna, with the orchestra led by the Prince’s Kapellmeister Anton Wranitzky. Making use of his rights, Lobkowitz had the symphony performed at his Jezeří chateau, North Bohemia, in the presence of Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia, who was passing through Bohemia within a diplomatic mission. In January 1805, Beethoven’s piece was played at the Palais Lobkowicz. Symphony No. 3 received its public premiere on 7 April 1805 at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna, with Beethoven himself conducting. The question remains as to whom the Italian dedication “composta per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grand Uomo” (composed to celebrate the memory of a great man) refers to in the score published in the autumn of 1806, already under the title “Sinfonia Eroica”. Today, it is generally assumed that the “great man” was Prince Louis Ferdinand, who died in the Battle of Saalfeld on 10 October 1806.

Beethoven‘s Symphony No. 3 would soon be branded a revolutionary work, deemed to be a landmark in terms of music, as well as a piece reflecting a great social upheaval. Back in 1839, someone wrote that “Beethoven projected in tones the tempests of the global revolution; with anxiety yet teeming with enthusiasm we listen to his audaciously approximating the boundaries of harmony itself.” Symphony No. 3 represents a watershed in Beethoven’s oeuvre and a key milestone in the development of symphonic music in general. An extraordinarily large-scale piece, the instruments it is scored for include three horns. Some consider the sheer number, unusual for the period in which it was written, to have been down to Beethoven’s deteriorating hearing, yet it is more likely to indicate the tendency to expand the orchestral sound, which came to full fruition (by means of technical improvements of the instruments’ design) in the Romantic era. The main theme is made up of tones of an arpeggiated six-four chord in E-flat major with a dissonant C-sharp chord, yet the seminal role in building the structure is played by two opening tutti chords as the rhythmic basis of the entire first movement. A new theme is introduced in the development section. The second movement is the first instance of a funeral march being used as an independent part of a symphony, while the third is one of the liveliest scherzos Beethoven ever wrote. Truly brilliant are the variations of the final movement. All in all, Beethoven’s Eroica is a ground-breaking masterpiece that paved the way to the grand symphonies the next generations of composers would create.