As a boy, Giovanni’s parents wanted to enrol him in the preparatory department of the Milan Conservatoire. According to the school, their son was too high-spirited, and he was not admitted as a violin student, but he soon more than made up for their disappointment. He studied the recorder, and while still a student, he joined with the lute player Luca Pianca in establishing Il Giardino Armonico—an ensemble that has won worldwide renown over its 40 years of existence in the field of the informed interpretation of early music.

Since 2014, Antonini and the ensemble have been working on the project Haydn 2032, presented by the Joseph Haydn Foundation in Basel. The goal is to record all 107 of the composer’s symphonies by his 200th birthday, for the first time on period instruments and on the basis of the latest research on how his works were originally interpreted.

However, Antonini’s knowledge does not hinder his unorthodox approach to music: “We can benefit from the fact that there no longer exists a ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’ orchestral sound or a single period instrument sound because there are also many of them. There is yet a third possibility—not only a musical, but also a human encounter between two worlds that create something new. It depends on the chemistry that can be created between the conductor and the orchestra”, he explains.

“My approach oscillates between that of a classic conductor when I give a composition’s tempo and lead it, but it is also important for me to give the players responsibility. I don’t want them to submit to my gestures, but instead to listen. When someone plays Bach unusually, it enriches my musical panorama. The meaning of music is to bring pleasure to listeners and musicians”, says Antonini, according to whom classical music has nothing to hide, especially the older music. In scores like those by Haydn or Vivaldi without many instructions, one has to discover lots of things, and that puts great demands on performers’ imagination.

Antonini speaks jokingly about the recorder being his toy: “On the one hand, playing it can be very easy: you blow, and a sound comes out. It gives you a feeling of deep satisfaction and is very relaxing. I would compare working with your breath this way to yoga. There almost isn’t any resistance in it, and the air flows naturally. When I’m tired after a rehearsal and play for about half an hour in my room, it’s very relaxing.”

Performers

Jan Fišer violin

Czech Philharmonic concertmaster Jan Fišer already exhibited his obvious musical talent as a child, winning many competitions (Kocian Violin Competition, Concertino Praga, UNESCO Tribune of Young Musicians, Beethoven’s Hradec etc.). He comes from a musical family, quite literally a family of violinists—his father is one of the most respected violin teachers in this country, and his younger brother Jakub plays first violin in the Bennewitz Quartet. Jan Fišer took his first steps as a violinist under the guidance of Hana Metelková, and he later studied at the Prague Conservatoire under Jaroslav Foltýn. He went through the famed summer programme of the Meadowmount School of Music three times, where he also met his future teacher, the concertmaster of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra Andrés J. Cárdenes. It was in the studio of that important professor who continued the great Ysaÿe–Gingold–Cárdenes tradition of violin pedagogy that Fišer graduated from the Carnegie Mellon University School of Music in Pittsburgh in 2003.

Just when he was deciding whether to remain in the USA or to return to the Czech Republic, the Prague Philharmonia announced an audition for the position of concertmaster. Fišer won the job and stayed with the orchestra for a full sixteen years, until he left the first chair of the Prague Philharmonia for the same position with the Czech Philharmonic, where he remains to this day alongside Jan Mráček and Jiří Vodička. He has also appeared as a guest concertmaster with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Bamberg Symphony, and the Deutsche Radio Philharmonie Saarbrücken Kaiserslautern; he also collaborates with important Czech orchestras as a soloist (Prague Philharmonia, Janáček Philharmonic in Ostrava etc.). He has assumed the role of artistic director of the Czech Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra.

Besides engaging in a wealth of orchestral and solo activities, he also devotes himself actively to playing chamber music. With pianist Ivo Kahánek and cellist Tomáš Jamník, he belongs to the Dvořák Trio, which has already enjoyed many successes at competitions (such as the Bohuslav Martinů Competition) and on concert stages both at home and abroad. Jan Fišer has appeared at festivals abroad and in famed concert halls worldwide not only as a soloist, but also as a chamber music player. For example, the Dvořák Trio has made guest appearances at the Dresden Music Festival and at renowned concert halls like the Berlin Philharmonie and Hamburg’s Elbephilharmonie.

Fišer’s French violin from the early 19th century is attributed to the violinmaker François-Louis Pique; the instrument has also been heard in recording studios: Jan Fišer records for television and radio, and he was one of the five laureates to take part in recording the CD “A Tribute to Jaroslav Kocian” for the 40th anniversary of the Kocian International Violin Competition. He is also following in his father’s footsteps as a pedagogue, serving as one of the mentors for the MenART scholarship academy, and he regularly teaches at music courses including the Ševčík Academy in Horažďovice and the Telč Music Academy.

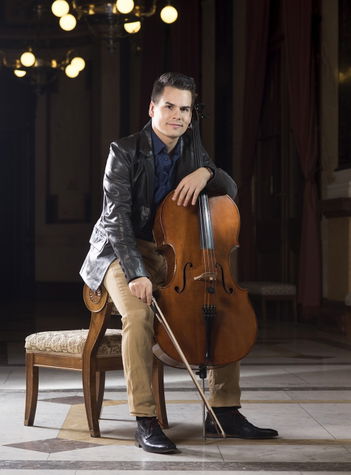

Václav Petr cello

One of the finest Czech cellists, Václav Petr has served as concert master of the Czech Philharmonic cello section for over a decade. He has performed as a soloist since the age of 12. As a member of The Trio, he has also devoted to chamber music.

Václav Petr learned the rudiments of viola playing at the Jan Neruda School in Prague from Mirko Škampa and subsequently continued to study the instrument at the Academy of Performing Arts in the class of Daniel Veis, graduating under the guidance of Michal Kaňka. He further honed his skills at the Universität der Künste in Berlin under the tutelage of Wolfgang Boettcher, and also at international masterclasses (in Kronberg, Hamburg, Vaduz, Bonn and Baden-Baden). He has garnered a number of accolades, initially as a child (Prague Junior Note, International Cello Competition in Liezen, Talents of Europe) and then in Europe’s most prestigious contests (semi-final at the Grand Prix Emanuel Feuermann, victory at the Prague Spring Competition).

At the age of 24, after winning the audition, he became one of the youngest concert masters in the Czech Philharmonic’s history. As a soloist, he has performed with the Czech Philharmonic, the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Prague Philharmonia, the Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava and the Philharmonie Baden-Baden.

Václav Petr has made a name for himself as a chamber player too. Between 2009 and 2020, he was a member of the Josef Suk Piano Quartet, with whom he received first prizes at the competitions in Val Tidone and Verona (Salieri-Zinetti), as well as at the highly prestigious Premio Trio di Trieste. In 2019, he, the violinist and concert master Jiří Vodička, and the pianist Martin Kasík formed the Czech Philharmonic Piano Trio, later renamed The Trio. During the Covid pandemic, they made a recording of Bohuslav Martinů’s Bergerettes (clad in period costumes), which would earn them victory at an international competition in Vienna.

Karolina Pancernaite piano

Karolina Pancernaite, a member of Czech Philharmonic from 2023, is a passionate and accomplished pianist from Lithuania with a rich international performance background. Starting her musical journey at the age of six, Karolina made her solo debut at 10 years-old, performing with the Brno Philharmonic Orchestra and a few years later with the Kaunas Symphony Orchestra in Lithuania.

She studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London with Christopher Elton. She was accepted with an entrance scholarship and received the Maud Hornsby Award for her excellent first-year attainment, before graduating with a 1st Class Honors Bachelor’s degree in 2017.

Karolina then moved to Glasgow, Scotland, to study at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland with Aaron Shorr and Petras Geniušas, where she was awarded the prestigious ABRSM scholarship. Whilst at the RCS, she won the Tony and Tania Webster Prize and received 3rd Prize in the Bamber Galloway recital competition. Currently Karolina is finishing her Master’s in Chamber Music at the Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien with Stefan Mendl.

She has given recitals in various festivals and concert halls throughout Europe including Steinway Hall in London, Kaunas Philharmonic Hall, Purcell Room Southbank Centre, Queen’s Hall in Edinburgh and Musikverein in Vienna. In 2019, Karolina was selected to join the European Union Youth Orchestra (EUYO) for 2019/20/21.

Karolina is an avid chamber musician as well. She is the pianist of the Cordelia Piano Trio with which she performed two recitals in the “Souvenir” concert series in the Brahms Saal, Musikverein and became the winners of the Café Bauhaus Award from the European Union Youth Orchestra for the “Collab” Project which she created alongside her trio partners. She has collaborated with many distinguished artists and ensembles such as the Chaos String Quartet.

For all her musical achievements, Karolina received a commendation from the President of Lithuania, Valdas Adamkus. She is also a featured artist of the Talent Unlimited, London.

Giovanni Antonini conductor, recorder

A native of Milan, Giovanni Antonini has long been acclaimed worldwide for his innovative and polished approach to performing the Baroque and Classical repertoire while fully respecting the precepts of historically informed interpretation. However, the path of early music was not his first choice of study. He had originally applied to the conservatoire as a violinist, and it was only because he did not succeed at his audition that he ultimately began studying the recorder, and he became a master of the instrument. It was thanks to his study of the flute at the Civica Scuola di Musica that Antonini fully discovered the world of Baroque music. In addition, as he himself recalls, it was a great advantage that as a flautist specialising in historical interpretation, he did not have many artistic models to rely on and simply imitate (after all, in the 1980s the field was still in its infancy), so he had to seek out his own interpretive approaches. He found further support in his studies at the Centre de Musique Ancienne in Geneva, but the urge never abandoned him to penetrate truly deeply into the music and to create his own language, which is now so appreciated for its uniqueness.

In 1985 he founded his own Baroque ensemble Il Giardino Armonico, with which he still appears all around the world in the dual role of soloist (whether on the recorder or the Baroque transverse flute) and conductor. Overall, perhaps the most ambitious project he threw himself into a few years back with the Basel Chamber Orchestra was to record the complete symphonies of Haydn, and to finish by the year 2032, the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth. The project Haydn2032, of which Antonini is the artistic director, is daring not only for its scope (Haydn wrote 107 Symphonies, so it is necessary to release 2 CDs with three or four symphonies every year!), but also because of the interpretive difficulties of Haydn’s music. “Haydn is very difficult to perform well because many of the interpretive paths can sound boring. But Haydn is not boring, it’s just the matter of finding the key to the correct interpretation”, explains Antonini. So far, 18 CDs have been issued, so the Haydn symphonic repertoire he has already recorded, rehearsed, or prepared has also influenced the programming of Antonini’s concerts in recent years.

Of course, Antonini does not overlook other greats masters of the 16th through the 18th centuries, whose works he has recorded with Il Giardino Armonico or performed in concert with such major orchestras as the Berlin Philharmonic, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw Orchestra, and the London Symphony Orchestra and with renowned soloists like Cecilia Bartoli, Giuliano Carmignola, Isabelle Faust, and Katia and Marielle Labèque. He also devotes himself to opera; in recent years, for example, we have been able to see him at Milan’s La Scala (Giulio Cesare), the Zurich Opera House (Idomeneo), and the Theater an der Wien (Rappresentatione di Anima, et di Corpo). He is also the artistic director of the Polish music festival Wratislavia Cantans and the principal guest conductor of the Basel Chamber Orchestra.

Compositions

Ludwig van Beethoven

Triple Concerto in C major for violin, piano, and orchestra, Op. 56

In 1802, at just 32 years of age, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) overcame a major crisis in his personal and professional life. Ill health, constant tinnitus, and worsening deafness did not offer much hope for the future for a young composer, conductor and, above all, virtuoso pianist. That year, he had spent the period from April until October in Heiligenstadt, then a village on the outskirts of Vienna, where he faced thoughts about his own mortality. Remaining to us as evidence of Beethoven’s fragile state of mind at the time, the “Heiligenstadt Testament” is a letter he addressed to his two brothers but never sent. In it, the composer admits that he had been considering a voluntary departure from this world, but the internalised confession had a cathartic effect on his mental state. After months of melancholy, depression, and doubts, Beethoven’s heroic period arrived with an advancement of his musical language, combining the classical traditions of Haydn and Mozart with emerging Romanticism. Between 1802 and 1812, he composed (among other things) five symphonies including his Eroica, the fate-laden Fifth, and the Pastoral, three piano concertos, a violin concerto, piano sonatas including the Appassionata and Les Adieux, and his only opera, Fidelio.

It was during this period of artistic flourishing that Beethoven met Archduke Rudolf, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II. The archduke was himself a skilled pianist, and he became Beethoven’s pupil and soon his generous patron as well. It is said to have been thanks to Rudolf’s financial and social support that Beethoven never accepted any offer of work that would have required him to stay away from Vienna for long periods. The composer rewarded his patron with music and dedicated more of his works to him than to anyone. Among the 14 works dedicated to the archduke are Beethoven’s Fourth and Fifth Piano Concertos, the aforementioned piano sonata Les Adieux, the Große Fuge for string quartet, and above all the monumental Missa solemnis, which Beethoven regarded as his greatest work according to a letter dated 1822.

Between 1803 and 1804, Beethoven also composed his Triple Concerto for violin, cello, piano, and orchestra for the future Archbishop of Olomouc, although it is not actually dedicated to him. According to the composer’s first biographer Anton Schindler, the archduke, just 16 years old at the time, was even supposed to have played the piano part at the premiere, as is suggested by the fact that of the three solo parts, the piano part is the least technically difficult. More recent scholarship has cast doubt on Schindler’s claim, but there is no clear evidence identifying the first performers.

While the Triple Concerto has long been overshadowed by Beethoven’s piano concertos, it definitely cannot be regarded as a work of lesser artistic value. At a time when the Romantic concerto genre was just taking shape with a highly prominent solo element, and when composers were seeking to balance the soloists and the orchestra, Beethoven set himself a difficult task by assigning solo parts to three different instruments. He took inspiration from the growing popularity of the piano trio, but he also had to deal with a whole range of sonic and formal pitfalls: finding a balance between the three instruments as carriers of the thematic material, conceiving their parts so they would not stand out too much, meanwhile keeping their different tone colours from getting lost in the orchestral texture.

The success of any performance of the Triple Concerto is always directly proportionate to the quality of the soloists, who must combine the intuition of chamber musicians, virtuosity, and sensitivity for the lyrical expression that is the basis for the slow second movement in particular. The conductor Herbert von Karajan made a major contribution to the work’s worldwide popularity in 1969 when he recorded it with a trio of legends: Oistrakh – Rostropovich – Richter. Ten years later, he recorded it again with pianist Mark Zeltser, cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, a rising star then just 13 years old. Appearing as this evening’s soloists are leading players of the Czech Philharmonic: concertmaster Jan Fišer, principal cellist Václav Petr, and pianist Karolina Pancernaite.

Antonio Vivaldi

Concerto No. 3 in D major “Il Cardellino”, Op. 10

Among all the genres of Italian Baroque music to which Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) devoted himself, two stand out: opera, regarded during the first half of the 18th century as the supreme musical form, and the instrumental concerto, thanks to which Vivaldi’s name remains familiar all around the world. The Four Seasons, a cycle of four violin concertos inspired by the transformations of nature in the course of the year, has brought immortality to the native of Venice who went on to become the court Maestro di Cappella in Mantua. In that work, Vivaldi brought the violin concertos to one of the genre’s historical pinnacles. He established the concerto’s standard three-movement form based on the contrast between a fast, a slow, and another fast tempo, and he enhanced the genre with sonically interesting orchestral accompaniments. Above all he combined virtuosity and technical demands with brilliantly melodic themes and a wide range of musical emotions.

Vivaldi also used a similar compositional procedure in other collections for violin as well as for oboe of flute. In 1728, five years after the release of his most famous work, his Six Flute Concertos, Op. 10, were also published. Like The Four Seasons, the first three have programmatic titles. La tempesta di mare describes a storm at sea and is dynamic and virtuosic like opera arias, in which analogies to forces of nature were a popular dramatic resource. Contrary to tradition, La notte has six movements and takes the listener through the night from a mysterious sunset, through the wild revelry of spirits, to meditative dreaming. Il Gardellino imitates the attractive trilling and chirping song of the goldfinch. The concerto sounds playful, moving in the highest register. Especially in the outer movements, the music is based on short, rhythmically striking motifs and plentiful melodic ornamentation.

Vivaldi’s flute concertos can be played on either a transverse flute or a recorder. For Il Gardellina, performers often choose the sopranino recorder, the smallest and highest-pitched version. Its penetrating sound and clear colour further enhance the concerto’s characteristic atmosphere.

Joseph Haydn

Symphony No. 54 in G major, Hob I:54

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), unlike his younger colleagues Mozart and Beethoven, did not come from a family of professional musicians. His mother was a cook, and his father was a wheelwright. Still, music was a natural part of his upbringing, and both Joseph and his younger brother Michael, who later likewise became a composer, devoted themselves to music from an early age. Being unable to afford funding their children’s systematic musical education, Joseph’s parents put the six-year-old boy initially in the care of his music teacher, then two years later he was enrolled in the boy’s choir at St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. It was there that his remarkable career began, and despite some initial setbacks, he eventually attained financial success, high social standing, and Europe-wide fame.

The scope of Haydn’s oeuvre is amazing even in comparison with the output of his contemporaries. He is said to have written nearly two thousand works including operas, oratorios, masses, concertos, and string quartets, but he has gone down in history primarily as the “Father of the Symphony”. He wrote an incredible 104 symphonies, the first in 1759, and the last nearly four decades later. However, the exact dating of many of his symphonies has not been preserved, so scholars have agreed on their assignment to categories reflecting the individual stages of the composer’s career, working successively for the Morzin and Esterházy families and then as a freelance musician.

Haydn reached one of the highpoints of his creative output while employed by the house of Esterházy, Hungary’s wealthiest and most powerful family. Between 1761 and 1791, the composer divided his time between Vienna, nearby Eisenstadt, and later the Esterháza Palace in the little Hungarian town Fertőd. Three quarters of the more than 100 symphonies he composed date from those thirty years, including the Symphony No. 54 in G major (1774). It was especially in Esterháza, once called the “Hungarian Versailles”, that Haydn had exceptionally favourable working conditions. On the one hand, he was somewhat isolated from the musical life of Vienna, but on the other hand he had an excellent, well-staffed orchestra at his disposal, constant demand for new works, and even an opera hall with seating for an audience of about 400. These circumstances enabled him to refine his musical language, to develop his approach to form, and to experiment with tone colours. For this reason, several of Haydn’s symphonies have descriptive titles, mirrored in their diverse and inventive thematic material and their vivid tone painting. Examples include the Symphony No. 31 in D major, nicknamed the “Hornsignal” because of its prominent use of an unusually large French horn section, or the “Farewell” Symphony No. 45 in F sharp minor, in which the musicians depart the stage one after another during the finale.

The Symphony in G major on this evening’s programme does not have any nickname, but it boasts rich orchestration and a strongly majestic character, especially in the first movement. The contrasting second movement brings a mood of intimacy with a series of brief motifs that pass through the whole orchestra, from the violins and violas to the woodwinds. The quick finale is sonorous and, in places, dramatic. The work foreshadows the masterpieces of Haydn’s maturity while also drawing aesthetic inspiration from the Enlightenment’s “Sturm und Drang” (“Storm and Stress”) movement.