1 / 6

Czech Philharmonic • Toronto

The Czech Philharmonic rarely visits Canada so this final concert of the tour will be even more heartfelt. Concertmaster Jan Mráček will take up the solo part in Dvořák’s Violin Concerto in the first half of the concert. In the second half, Chief Conductor Semyon Bychkov will lead the Czech Philharmonic in Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, which they recently recorded together to international acclaim.

Programme

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor

Performers

Jan Mráček violin

Semyon Bychkov conductor

Czech Philharmonic

To purchase online, visit the event presenter's website.

Performers

Jan Mráček violin

The Czech violinist Jan Mráček was born in 1991 in Pilsen and began studying violin at the age of five with Magdaléna Micková. From 2003 he studied with Jiří Fišer, graduating with honors from the Prague Conservatory in 2013, and until recently at the University of Music and the Performing Arts in Vienna under the guidance of the Vienna Symphony concertmaster Jan Pospíchal.

As a teenager he enjoyed his first major successes, winning numerous competitions, participating in the master classes of Maestro Václav Hudeček – the beginning of a long and fruitful association. He won the Czech National Conservatory Competition in 2008, the Hradec International Competition with the Dvořák concerto and the Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra in 2009, was the youngest Laureate of the Prague Spring International Festival competition in 2010, and in 2011 he became the youngest soloist in the history of the Czech Radio Symphony Orchestra. In 2014 he was awarded first prize at Fritz Kreisler International Violin Competition at the Vienna Konzerthaus. When the victory of Jan Mráček was confirmed, there was thunderous applause from the audience and the jury. The jury president announced, “Jan is a worthy winner. He has fascinated us from the first round. Not only with his technical skills, but also with his charisma on stage.”

Jan Mráček has performed as a soloist with world’s orchestras, including the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony, Symphony of Florida, Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra, Kuopio Symphony Orchestra, Romanian Radio Symphony, Lappeenranta City Orchestra (Finland) as well as the Czech National Symphony Orchestra, Prague Symphony Orchestra (FOK), Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra and almost all Czech regional orchestras.

Jan Mráček had the honor of being invited by Maestro Jiří Bělohlávek to guest lead the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in their three concert residency at Vienna’s Musikverein, and the European Youth Orchestra under Gianandrea Noseda and Xian Zhang on their 2015 summer tour. He has been a concertmaster of the Czech Philharmonic since 2018.

In 2008 he joined the Lobkowicz Piano Trio, which was awarded first prize and the audience prize at the International Johannes Brahms Competition in Pörtschach, Austria in 2014.

His recording of the Dvořák violin concerto and other works by this Czech composer under James Judd with the Czech National Symphony Orchestra was recently released on the Onyx label and has received excellent reviews.

Jan Mráček plays on a Carlo Fernando Landolfi violin, Milan 1758, generously loaned to him by Mr Peter Biddulph.

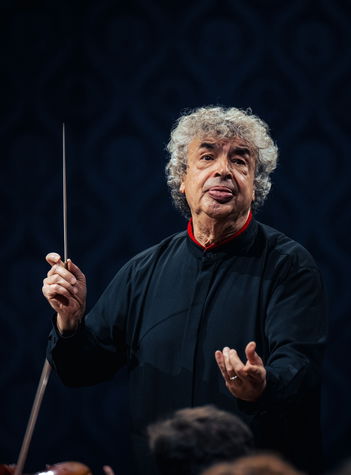

Semyon Bychkov conductor

In addition to conducting at Prague’s Rudolfinum, Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic in the 2023/2024 season, took the all Dvořák programmes to Korea and across Japan with three concerts at Tokyo’s famed Suntory Hall. In spring, an extensive European tour took the programmes to Spain, Austria, Germany, Belgium, and France and, at the end of year 2024, the Year of Czech Music culminated with three concerts at Carnegie Hall in New York.

Among the significant joint achievements of Semyon Bychkov and the Czech Philharmonic is the release of a 7-CD box set devoted to Tchaikovsky’s symphonic repertoire and a series of international residencies. In 2024, Semjon Byčkov with the Czech Philharmonic concentrated on recording Czech music – a CD was released with Bedřich Smetanaʼs My Homeland and Antonín Dvořákʼs last three symphonies and ouvertures.

Bychkovʼs repertoire spans four centuries. His highly anticipated performances are a unique combination of innate musicality and rigorous Russian pedagogy. In addition to guest engagements with the world’s major orchestras and opera houses, Bychkov holds honorary titles with the BBC Symphony Orchestra – with whom he appears annually at the BBC Proms – and the Royal Academy of Music, who awarded him an Honorary Doctorate in July 2022. Bychkov was named “Conductor of the Year” by the International Opera Awards in 2015 and, by Musical America in 2022.

Bychkov began recording in 1986 and released discs with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bavarian Radio, Royal Concertgebouw, Philharmonia Orchestra and London Philharmonic for Philips. Subsequently a series of benchmark recordings with WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne featured Brahms, Mahler, Rachmaninov, Shostakovich, Strauss, Verdi, Glanert and Höller. Bychkov’s 1993 recording of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with the Orchestre de Paris continues to win awards, most recently the Gramophone Collection 2021; Wagner’s Lohengrin was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Year (2010); and Schmidt’s Symphony No. 2 with the Vienna Philharmonic was BBC Music Magazine’s Record of the Month (2018).

Semyon Bychkov has one foot firmly in the culture of the East and the other in the West. Born in St Petersburg in 1952, he studied at the Leningrad Conservatory with the legendary Ilya Musin. Denied his prize of conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic, Bychkov emigrated to the United States in 1975 and, has lived in Europe since the mid-1980’s. In 1989, the same year he was named Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, Bychkov returned to the former Soviet Union as the St Petersburg Philharmonic’s Principal Guest Conductor. He was appointed Chief Conductor of the WDR Symphony Orchestra (1997) and Chief Conductor of Dresden Semperoper (1998).

Compositions

Antonín Dvořák

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 53

Personal relationships, friendships, and mutual respect among individuals leave a more tangible imprint on history than one might expect. An illustrative chapter of music history involved Fritz Simrock, Antonín Dvořák, Johannes Brahms, Robert and Clara Schumann, and Joseph Joachim.

Among the compositions for solo instrument and orchestra by Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904), three concertos stand out: the Piano Concerto in G minor (Op. 33), the Violin Concerto in A minor (Op. 53), and the Cello Concerto in B minor (Op. 104). The first two date from almost the same period and were both actually published in 1883, but they underwent a different genesis. While Dvořák apparently came up with the idea of composing the early version of the piano concerto in 1876 on his own, perhaps fondly imagining Karel Slavkovský at the piano, the stimulus for writing the Violin Concerto in A minor was external. The publisher Simrock commissioned the increasingly popular Czech composer to write another composition of “Slavonic” character. The Czech Suite, Op. 39, the Slavonic Rhapsodies, Op. 45, the Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, and the String Quartet in E flat major, Op. 51 were all earlier works by Dvořák that were popular items on the sheet music market and were influenced by the melodic and rhythmic patterns of the folk music of the Czechs, Moravians, and other Slavic peoples. The violin virtuoso, conductor, and director of the Hochschule für ausübende Tonkunst Joseph Joachim, whom the composer had met in early April 1879 in Berlin, also supported the idea of a new concerto. The concerto’s dedication to Joachim shows Dvořák’s regard for the chance to collaborate with the legendary violinist and pedagogue.

Dvořák began composing his violin concerto in 1879 while spending the summer in Sychrov. Two years earlier he had left his poorly paid position as the organist at the Church of Saint Adalbert in Prague’s New Town, and now he was devoting himself solely to composing. The repeated awarding of a state stipend in support of artists made it easier for him to take that step, and it also led to his friendship with Johannes Brahms, who in turn facilitated Dvořák’s contract with Simrock, which was of vital importance to him. By the end of the 1870s, Dvořák had established himself at home and abroad. However, the path to the definitive version of the violin concerto was not easy: Dvořák’s consultations with Joachim dragged on (the composer waited more than two between the spring of 1880 and the autumn of 1882 year for Joachim’s reaction), and the publisher also had conditions through his advisor Robert Keller. Paradoxically, as it turned out, Joachim, who was supposed to have been the first interpreter of the work, and who made changes in particular to the form taken by the solo part, probably never played Dvořák’s Violin Concerto in public. František Ondříček gave the premiere in October 1883, and after the successful Prague performance with the orchestra of the National Theatre, he also introduced the composition to the enthusiastic Viennese public that December with the Vienna Philharmonic and with Hans Richter on the conductor’s podium. Ondříček then continued to promote the Violin Concerto in A minor throughout his stellar career.

Dvořák went about integrating the orchestra with the solo part similarly to his great model Brahms, whose Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, dates from about the same time. Brahms also dedicated his concerto to Joachim, who premiered it in January 1879. In both cases, the strongly contoured orchestral sound is combined with a solo violin part that is technically difficult, but also richly expressive. Dvořák displays mastery of orchestration, warmth of melodic writing, and vigorous rhythm. The first movement (Allegro ma non troppo) is in an ambiguous sonata form without a recapitulation, and it is linked directly to the lyrical slow movement (Adagio ma non troppo); this smooth attacca transition was one of the points under discussion during the revisions. The Adagio is in ternary form with variations, and its mood is highlighted by the “pastoral” key of F major. The energetic third movement (Finale. Allegro giososo, ma non troppo) employs the rhythm of the furiant, a Czech folk dance, with a melancholy dumka providing contrast in the middle section.

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 5 in C Sharp Minor

The works of Gustav Mahler are inseparable from his relationship with nature. He needed nature and sought it out, expecting it to provide him with “the basic themes and rhythms of his art”, and he compared himself with a musical instrument played by “the spirit of the world, the source of all being.” Just by looking at photographs of the places where he drew energy for composing, we can hardly avoid the impression that there is an intrinsic link between those natural surroundings and the composer’s music. Practical reasons also played a part; Mahler the conductor, always more than 100% devoted his work, could only find the peace and concentration he needed for composing during the summer holiday.

The composer began writing his Fifth Symphony in the summer of 1901 in the Austrian village Maiernigg beside Lake Wörth (Wörthersee), where he had a villa built along with a “hermit’s hut” for composing. By then, he was already in his fifth year at the helm of one of Europe’s most prestigious cultural institutions, the Court Opera in Vienna. This time, however, besides rest, he also needed to recover his health; in February he had nearly died of severe hemorrhoidal bleeding, and his life was saved by a prompt surgical procedure: “As I wavered at the boundary between life and death, I was wondering whether it wouldn’t be better to be done with it right away because everyone ends up there eventually”, he wrote later on.

Death seems to have been at Mahler’s heels from his childhood—seven of his twelve younger siblings did not live to the age of two, his brother Ernst died at age 13, and in 1895 Otto committed suicide at the age of 21. Four years later, the composer buried both of his parents and his younger sister Poldi. Thus, we are not surprised by the unusual number of funeral marches in his works, nor is this the first time that entirely contrasting music came into being in an idyllic environment: the last song of the collection The Youth’s Magic Horn titled The Drummer Boy, three of his Kindertotenlieder, four more songs to texts by Rückert, and the first two movements of a new symphony. “Their content is terribly sad, and I suffered greatly having to write them; I also suffer at the thought that the world shall have to listen to them one day”, he told his devoted friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner (1858–1921). About his symphony, he further noted that it would be “in accordance with all rules, in four movements, each being independent and self-contained, held together only by a similar mood.” Bach’s counterpoint became another important source of inspiration: “Bach contains all of life in its embryonic forms, united as the world is in God. There exists no mightier counterpoint”, he declared; he was spending up to several hours a day studying polyphony.

Suddenly, however, the composer’s life faced a disruption on a cosmic scale. Who knows how the symphony might have turned out if on 7 November 1901 he had not made the acquaintance of an enchanting, musically talented, and undoubtedly very charismatic woman named Alma Schindler (1879–1964) at a friendly gathering. She instantly won over Gustav with her directness, and she wrote in her diary: “That fellow is made of pure oxygen. Whoever gets close to him will burn up.” They were betrothed in December, Alma became pregnant in January, and the wedding took place on 9 March 1902 at Vienna’s Karlskirche in the presence of a small group of family and friends. The couple then embarked on a happy yet complicated period of their lives…

That summer in Maiernigg, Mahler composed the song Liebst du um Schönheit (If you love for beauty) for his wife, and he inserted into his Fifth Symphony one of his most intense and popular slow movements, the Adagietto. The symphony’s premiere took place on 18 October 1904 in Cologne under the composer’s baton. Audience members whistled at the concert to show their disapproval, and as an example of one of the many negative reviews, we can quote Hermann Kipper, according to whom the first movement was too long and the second movement contained many “unmusical” passages full of “appalling cacophony”; according to him, the composer’s brain “finds itself in a constant state of confusion.” After the premiere, Mahler commented laconically: “No one understood it. I wish I could conduct the premiere 50 years after my death.” The symphony was again unsuccessful the following year at performances in Dresden, Berlin, and Prague, where it was played on 2 March 1905 by the orchestra of the New German Theatre (now the State Opera) led by the composer and conductor Leo Blech (1871–1958). The symphony got its first truly warm reception on American soil on 24 March 1905, when Frank Van der Stucken conducted the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Performances followed in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, making Mahler’s music increasingly familiar in American circles before the composer himself came there in 1907.

Within the composer’s oeuvre, the Fifth Symphony represents a turning point. Although there continue to be thematic connections with his songs, we no longer find a vocal component in Mahler’s orchestral works with the exceptions of the Eighth Symphony and Das Lied von der Erde. Part I of the approximately 60-minute work consists of two dark, gloomy movements. First, we hear the famous trumpet fanfare announcing death and ushering in a funeral march. The calm, slow motion illuminated by the woodwinds playing a theme in the major mode is disrupted by a wildly dramatic section. Heaviness and dense orchestral sound alternate with introspective passages that reflect upon feelings of loss. The music extinguishes itself nearly in a state of despair, whereupon the next movement breaks forth vehemently (Moving stormily), in which a cantabile theme later appears, accompanied by sobbing winds. The two main ideas are later merged into a triumphant stream of brass, but once again the music leads us back into a state of tense anxiety.

Part II of the symphony consists Mahler’s vast Scherzo. Despite the music’s dance-like character and the absence of the composer’s usual irony, shadows of sadness, again entrusted to the winds, flit past us in this movement as well. Part III of the symphony opens with the intimate Adagietto for strings, made especially famous by Luchino Visconti’s film Death in Venice. The soothing music seems to disperse any the clouds of distress. Then in the bucolic, unrestrained finale, the composer broadly develops several themes, the third of which then leads to a magnificent brass chorale.