1 / 6

Vienna’s Musikverein, Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw, London’s Barbican Centre, the Philharmonie de Paris, and the Concertgebouw in Bruges. Led by Chief Conductor and music director Semyon Bychkov, the Czech Philharmonic has completed its spring tour, bringing the music of Mozart, Mahler, and Shostakovich to some of Europe’s most renowned concert halls.

Take a look at how it all unfolded!

13. 3. 19:00 Prague

On its European tour, the Czech Philharmonic played eight hours of Shostakovich, nearly four hours of Mahler, and just under two hours of Mozart. In five cities across five countries, about 15,000 people—and one dog—listened to us. A total of 101 philharmonic musicians, three soloists, and one Maestro traveled by train, bus, and plane, covering roughly 3,000 kilometers as the crow flies.

Now, all members of the tour are back with their loved ones, looking forward to something that was in short supply on the road—a quiet evening off.

12. 3. 13:00, Bruges

The life of a musician—such a bohemian dream! Or so the stereotype goes.

Truth be told, not so much on tour. Yes, some members of the orchestra enjoy a drink or two after a concert to help them unwind. But overall, discipline prevails. Many politely decline invitations for a nightcap, and when asked how they spend their free time, they mostly mention walks, museums, and culinary experiences.

"If you go partying after a concert, you’ll pay the price the next day," explains Chief Conductor Semyon Bychkov. "A musician’s life is absolutely wonderful, but even though it seems like we travel the world, we don’t actually see much of it—just the hotel room and the concert hall," he describes.

Find out what a day on tour looks like for Semyon Bychkov in the video.

11.03. 22:00, Philharmonie de Paris

The most formally dressed classical music audience can be found at the opera in Olomouc. Without a walking cane, cufflinks, and a hand-tied bow tie, you might feel like a poor relative. The farther west you go, the more casual the dress code. Ties are still worn in Brno, but in Vienna, they’ve been abandoned—though shirts and dresses still hold their ground. If you showed up in London or Paris dressed as you would for the Musikverein, you’d look like a waiter. In the Concertgebouw, like a hallucination.

Do you have a strong opinion on the matter?

Please send us a fax. Or just drop us a message on Instagram.

Different places, different dress codes, different customs. In Prague’s Rudolfinum, you won’t be allowed into the hall with your coat on. In London’s Barbican or in Paris, cloakrooms are optional—coats are draped over empty seats or rustle in people’s arms throughout the concert. The British have no qualms about bringing in a pint of beer or a glass of wine. Surprisingly, it doesn’t cause much disturbance—unlike the popcorn at the Metropolitan Opera.

But don’t even think about pulling out your phone—if you do, a supervisor will rush over, shine a flashlight in your face, and menacingly run a finger across their throat. In La Scala, on the other hand, they have an app for reading opera subtitles. It doesn’t emit any light, and its main advantage is that it automatically switches your phone to airplane mode—so no unwanted rings. Unlike at the Barbican, where an iPhone’s Marimba ringtone cut off the first attempt at an encore. Oh well, everyone laughed, including Semyon Bychkov, and they started over.

While in Vienna, it’s common to stroll from the upper gallery to the front railing for a closer look at the conductor’s gestures, in Paris, even the slightest fidgeting can earn you a strangling from behind. On the other hand, few people dashed out of the hall immediately after the last note, ignoring the curtain call. The metro won’t wait.

And just when you think nothing can surprise you anymore, the French break into a football-style chant of applause after Mahler.

Gentlemen, much appreciated.

10.03. 20:00, Philharmonie de Paris

As the posters in the Barbican remind us, every person is different. Some have eggs for breakfast, others prefer sausages. One dresses in cotton, another in latex. There are those who listen to disco. But two things unite us all: we breathe oxygen and cough between the phrases of a symphony. Yet when the Czech Philharmonic starts to play, silence falls—like in a church.

You’ve already read about London’s Elgar. Another highlight of the tour was Shostakovich’s Fifth in Paris. One of those concerts where the listener feels they are touching musical perfection. And the audience sensed it, delivering one of the most focused listening experiences ever. A gesture musicians must value even more than today’s somewhat overused standing ovations.

It was such an intense artistic experience that it briefly knocked out the phone signal. Finding the right metaphor to describe it is no easy task. But fine. It was like—Winnetou.

10.03. 16:00 Philharmonie de Paris

Many didn’t believe in it at all—and it almost wasn’t built. On the outskirts of Paris, in a troubled district, far from the refined audience typically drawn to this kind of entertainment. And the cost—initially planned at 170 million euros, but in the end, a staggering 390 million.

When the project was halted halfway through construction, it was hanging by a thread. Things only started moving again after the director of the Orchestre de Paris took his complaint to the top—to then-President Sarkozy. Sarkozy, in turn, vented his political frustration on his Prime Minister, Fillon, and today, the Philharmonie de Paris stands as an extraordinary example of urban success.

Star architect Jean Nouvel—who, incidentally, also designed the building at Prague’s Anděl—created what is undoubtedly one of the most stunning European structures of this century. It resembles a massive sculpture, a jagged boulder, or a rolling mountain. Its surface is covered with 340,000 aluminum tiles that evoke a flock of grayish birds. In the daylight, they shimmer and glisten. And from the rooftop, there’s a spectacular view of Paris.

10.03. 10:00, English Channel,

50 metres below the seabed

“Dear passengers, as you can see, the train is not moving as fast as usual. The train is moving slow. This is due to our driver Francois was refused to go to the fast line. We hope we get to the fast line soon. Than the train will be moving fast again. Thank you.”

“Dear passengers, coffee machine in compartment 9 is not working. This is due to technical problems. From this reason, coffee, cappuccino and things like that are not available at the moment. After Brussels there will be coffee in compartment 8. Thank you for your understanding and sorry for the inconvenience.”

9. 3. 16:00 London

On paper, it sounds fantastic: a two-week business trip to Vienna, Amsterdam, London, Paris, and Bruges, performing in the most beautiful concert halls in Europe. Who would complain? But then you actually have to, well, endure the whole journey…

“Sometimes it’s tough because you have to catch a flight in the morning, transfer to another city, take a bus to the hotel, and perform in the evening. And the next day, it starts all over again,” says Jan Fišer, describing the life of a touring musician. As concertmaster, he has additional responsibilities on top of that.

“I help interpret between the conductor and the orchestra and vice versa. Then there’s the public aspect—representing the orchestra at various events—but otherwise, it’s not that different from what audiences know from home,” he explains.

And another concern: Jan Fišer plays a very valuable, moreover borrowed instrument. He prefers not to send it with the rest of the equipment in a truck. “My violin is part of my identity, my companion. I want to have it with me at all times. In the hotel, it has a place of honor,” he admits, revealing that on tour, he falls asleep and wakes up with his instrument always in sight.

Amid the constant travel and tight schedules, getting enough rest is crucial. That’s why he’ll decline an invitation for a drink in favor of a pre-concert walk. He could easily work as a London tour guide—he navigates the half-hour walk from his hotel to the Barbican without needing a map. “I’ve been here a few times…” he chuckles.

Recently, he visited with his family, so he has already explored the landmarks, museums, and galleries. “I’d rather go to the park. Everything will start blooming soon—it’s going to be beautiful,” he says, looking forward to his day off. And that brings us back to the question of how to unwind on long tours. “You try to make the most of every minute. Because when you step onto the stage and start playing, you need to be fully focused, forget everything else, and think only about the audience and the music.”

Like most musicians, Jan Fišer looks forward to performing in stunning concert halls. His favorite is the Musikverein—not just for its aesthetic beauty but also for its historical significance. What other place in the world better embodies the tradition of musical Romanticism? Among modern halls, he’s particularly fond of Tokyo’s Suntory Hall.

For musicians, concert halls are primarily workplaces—they need to understand them acoustically. “We know most halls well, so adaptation is quick. The most important thing is tuning into each other so that we feel connected, listening and responding to one another. That’s what makes the music sound cohesive to the audience,” Fišer explains.

He shares a memory from the Elbphilharmonie, where he performed with a trio. He was staying at a local hotel. “I was lying in the bathtub, looking out the window at the ships,” he recalls. And he adds that Prague, too, deserves its own Vltava Philharmonic Hall. “The orchestra needs a new hall—even Mahler’s music is too much for Dvořák Hall. Still, I always love returning to the Rudolfinum. There’s no place like home.”

8. 3. 21:30, London, Barbican

The orchestra, after performing Shostakovich on tour, has added Nimrod from Elgar’s Enigma Variations to the program. It probably won’t surprise you that the piece received the biggest ovation in London. The British are as proud of their Elgar as we are of Dvořák and Smetana, but this cultural reference carries an even deeper meaning on the island.

Since 1919, Nimrod has been played on Remembrance Day, marking the end of the Great War and honoring its fallen. It accompanied soldiers returning from the Second World War and is often heard at funerals and royal ceremonies. It even opened the Olympic Games. The piece features in major war films—most recently in The King’s Speech and Dunkirk. Over time, it has become a deeply felt musical symbol of English patriotism.

Still, we weren’t prepared for how profoundly it would affect the sold-out Barbican audience. At least half the hall recognized Nimrod within the first few bars, let out a deep sigh, and surrendered to emotion. Some people broke into open tears. After an hour of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, a cathartic release.

Next time you pin on a red poppy, play some Elgar to go with it.

7. 3. 22:00 London, Barbican

The buses that were supposed to arrive didn’t, and instead, the ones that weren’t supposed to came. Late, of course. And the ride to the hotel didn’t take an hour—it took two. Part of the multimedia crew wasn’t allowed on the plane, and their luggage went missing. The taxi never made it to its destination due to road closures. In southern Belgium, a bridge collapsed, and an unexploded WWII bomb brought trains between the continent and the islands to a halt.

It wasn’t just transport—electronics, too, seemed restless that day. Phones rang, but when you picked up, there was no one there. The GPS insisted we were in the middle of the English Channel. Watches beeped not on the hour, but at 37 minutes past. Pedometers, without exception, displayed exactly 6,666 steps. Our pocket barometers reported pressure levels more suited to Jupiter’s moons.

It all made sense only after the concert at the Barbican. He had come—the one whose name must not be spoken.

7. 3. 11:00 Somewhere over Europe, 10.000 meters above the ground

“Even before the war, in Leningrad there probably wasn’t a single family who hadn’t lost someone, a father, a brother, or if not a relative, then a close friend. I had to write about it, I felt it was my responsibility, my duty. I had to write a requiem for all those who died, who had suffered. I had to describe the horrible extermination machine and express protest against it.”

– Dmitri Shostakovich

On November 21, 1937, in Soviet Leningrad, Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D minor was performed for the first time. The atmosphere in the hall was tense. And it wasn’t just the collective anticipation that naturally accompanied the premiere of a major symphonic work by a renowned composer. Everyone present knew that Shostakovich had not premiered anything in two years—his music had fallen out of favor with Stalin.

During the height of the Great Purge, Shostakovich’s life was at stake. Many of his acquaintances, friends, and even relatives had already perished. Yet Stalin recognized that Shostakovich was a world-famous composer whose works were performed in prestigious concert halls across the globe. Rather than destroying him, the regime sought to reshape him, to tame him. Whether or not Shostakovich allowed himself to be tamed is a question each listener must answer for themselves.

The suitcase he had kept packed since the 1930s—just in case—remained untouched until 1969. Six years later, he passed away. That same year, in 1975, a young 23-year-old conductor named Semyon Bychkov fled the Soviet Union.

“Fifty years ago, I was faced with the need to break free from a dictatorship. Today, the confrontation between life and death is even sharper than it was half a century ago. The fight for our most fundamental human values—now under attack by the evil of fascism—has reached a point none of us have ever experienced before,” says the chief conductor and music director of the Czech Philharmonic.

That is one of the reasons we are now touring Europe with Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5. After the concerts, when we speak with audience members in the foyer, they often interpret this landmark work of modern music in a political light. And they tell us they are afraid.

6. 3. 01:00 Amsterdam

We have no idea why, but people keep asking us if we forgot something. This time, we didn’t.

The Czech Philharmonic is traveling with 80 cases packed with musical instruments, sheet music, shoes, tailcoats, gowns, and all the technical gear carefully handled by our stage managers, Franta Kuncl and Honza Pávek.

Watch the video from the road between Vienna and Amsterdam while these two are already setting up the stage in London.

"You know, when you're working as a team, the other guy takes care of whatever you don’t have time for."

05.03. Amsterdam, Concertgebouw

For a long 23 years, the Czech Philharmonic hadn’t played at the Concertgebouw—until now. And it shows. In Vienna or London, Czech musicians know exactly where to find their instrument cases in the backstage maze, which hallway leads to the right dressing room, and where to grab the nearest coffee. But this time, they’re a bit lost. Not on stage, though—there, everything is just as it should be. Shostakovich feels at home everywhere.

Here, however, it would be written as Sjostakovitsj, just like on the posters outside. Unlike the Haydns, Dvořáks, Bachs, and Mendelssohns, though, you won’t find his name engraved on the walls around the Grote Zaal. That’s because in 1888, when the first concert was played here, he hadn’t been born yet. The most eye-catching names are those of Röntgen, Dopper, Zweers, Wagenaar, Pijpee, Schuijt and so on, of which even native Dutchmen know little. It's like finding a bust of Jozef Richard Rozkošný in the Prague’s National Theatre. Only Deipenbrock was lucky enough to be friends with Mahler...

The acoustics of the magnificent Dutch hall are legendary. A quick Google search will turn up rapturous praise from famous conductors, architectural studies, popular science articles, and heated debates among audiophiles. They say that the Concertgebouworkest developed its signature velvety string sound precisely by rehearsing in this inspiring space—just as insiders claim that the refinement of the Czech Philharmonic’s woodwinds is shaped by the sound of the Rudolfinum.

And yet, during rehearsal, something hits you right in the ears. There’s just too much sound—every forte rolls over you like a wave. A local marketing manager explains that the empty hall has a reverberation time of 2.8 seconds. That’s why the Concertgebouworkest rehearses with a massive velvet curtain across the middle of the auditorium—though for a half-hour acoustic rehearsal, it’s not put up. No need to worry, he assures us. Once the audience arrives, the reverberation will drop to 2.2 seconds, and our ears will be at peace.

And he’s right. When two thousand people settle into a space the size of two Rudolfinums, the sound transforms completely—leaving the ears in shock once again. It’s like putting on glasses for the first time. A breathtaking experience that every classical music lover should have at least once. Even the applause sounds spectacular—especially the standing ovation from an audience that, by Czech standards, is strikingly young. Heel erg bedankt!

05.03. Amsterdam

"In the past, international promoters almost exclusively wanted us to play Czech music—they were reluctant to entrust us with anything else. But we thought it would be great if we remained the most authentic interpreters of Czech repertoire while also earning trust as a top-tier orchestra for international works. And I think we're succeeding quite well in that regard, which is what sets our current tours apart from previous ones," explains Robert Hanč, the General Manager and Artistic Director of the orchestra, who is responsible for the Czech Philharmonic's dramaturgy.

Under Bychkov, the orchestra has already made its mark with Tchaikovsky and continues to establish itself with Mahler. Recently, Thierry Escaich was performed alongside Bartók and Stravinsky in Budapest and Zagreb, while Bryce Dessner featured in Vienna and Bucharest. Now, it is time for a composer born in St. Petersburg, whose passing will mark 50 years this August. And according to Austrian critics, we’re doing quite well with Shostakovich.

“Bychkov managed to blend a touch of subtle bitterness into the beautiful sound.”

“The second movement, with its ironic exaggerations and seemingly playful spirit masking defiance and pain, came across as sophisticated in the Czech Philharmonic’s interpretation.”

“The orchestral sound can be delicate and refined, yet when needed, it transforms into the sharp, unmistakably Shostakovich-like expression, where bitter undertones resonate through forceful motifs.”

“In the Largo, Bychkov carefully shaped a sense of tragedy—shy, yet inevitably reaching outward—with great attention to detail.”

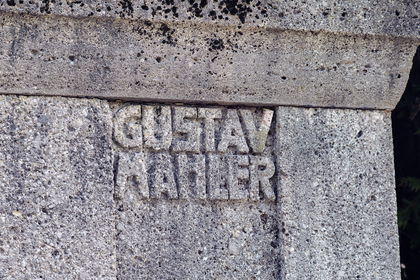

04.03. Vienna, Grinzinger Friedhof

In his book Verdi: A Novel of the Opera, Franz Werfel created a fascinating secondary character—the opera-loving Marquis Gritti. A centenarian, he attends the theater every evening without exception, carefully preserving programs, singer portraits, and rare artifacts as testaments to his passion. Convinced that strict discipline will allow him to live forever, his peculiar vitality inspires both awe and unease in those around him.

Though Prague-born Werfel set his novel in Venice, we’d wager he drew inspiration from Vienna as well, where he lived from the end of World War I and where he met his future wife, Alma Mahler. After all, the walls of the Musikverein and the State Opera still echo with the same musical fervor that once consumed Gritti.

Anyone sitting in the Golden Hall, settling into a small, creaky old seat, and looking toward the stage—where music has been performed at the highest artistic level for over 200 years—can’t help but feel this deep-rooted tradition.

Not only has little changed here, but even the smallest rituals endure: concertgoers walk past the same churches, on the same day, at the same hour; tickets are bought at the same box offices; people still jostle for standing-room spots and scramble toward ushers when unsold seats in the stalls become available. When Franz sat beside Alma, dreaming up his novel, he experienced much the same as we do today.

And he listened to the same music. Tonight, the Czech Philharmonic performed Mahler’s Fifth Symphony. It is now a staple of the symphonic repertoire, but when Gustav died, it was far from certain that his work would stand the test of time. It was thanks in no small part to Alma—both Gustav’s and Franz’s—that his legacy was tirelessly championed until her last days. That’s why we visited their graves in Vienna. Franz, sadly, rests elsewhere—there wasn’t time for him this trip. Next time.

Even the core message of Werfel’s novel remains strikingly relevant. Marquis Gritti adored only the “golden age of opera”—the old Neapolitan masters, Cimarosa, Zingarelli, and Gazzaniga, perhaps Bellini at most. But reformers like Wagner and Verdi? Enemies! He found their plots incomprehensible and dismissed their music as “confused noise.” To Gritti, opera was an art form meant to remain perfect, untouched by experiments that only composers and a handful of academics could appreciate.

Sound familiar?

03.03. Musikverin

Every good band has a hit, a smash, or at least an evegreen. Banger, Knaller, przebój, succès, sucesso, éxito, 名曲, 热门歌曲 či लोकप्रिय गीत. Something that everyone subconsciously knows, with a strong and memorable melody that pulls you in and makes you want to sing it over and over again. For example, the Czech Philharmonic has Mahler's Fifth Symphony.

Semyon Bychkov first conducted it for Prague’s subscription audience in 2021, and the response was so enthusiastic that we had to bring it back this season for subscribers in another series to enjoy as well.

Of course, a recording was made. Leading global critic Norman Lebrecht gave it a full rating, calling it proof that the orchestra, under its current Chief Conductor, is “setting the pace for Mahler recordings this decade.”

And so now we’re taking Mahler’s Fifth around the world. After New York and Toronto it’s coming with us to London and Paris. And just moments ago, it resounded in Vienna. You can probably guess how it was received. After all, it’s our hit!

02.03. Musikverein

Weekends in Vienna follow a clear tradition: schnitzel first, then straight to classical music. Afternoon subscription concerts are offered not only by the Vienna Philharmonic but also by other local orchestras, so it’s no surprise that on a Sunday at 3.30 PM, the Großer Saal fills up almost to the last seat. That means 1,700 seated and 300 standing attendees.

The Musikverein staff point out that the real connoisseurs can be found in the standing sections. Many have secured their spots over the years and fiercely defend them from tourists. Unlike at the Opera, however, no one ties scarves to the railings here.

Shostakovich, in any case, strikes a chord with them. Sheku Kanneh-Mason bows five times before offering a tender encore full of shimmering overtones (Edmund Finnis: Prelude III)—even more captivating live than on recording. The Fifth Symphony unfolds with the precision of slicing a three-tier cake with a laser. Astonishingly exact. But it’s the orchestral encore that truly lifts the audience from their seats: Elgar’s Nimrod.

A sight to behold. As Elgar’s first heart-wrenching notes emerge, a couple on the balcony reaches for each other’s hands, a man in the sixth row removes his glasses and wipes away a tear, and the elderly gentleman behind him closes his eyes, tilts his head back, and sinks into his wistful smile. In the cloakroom, conservatory students from northern Spain say it was the most beautiful concert they’ve ever heard. Maybe they’ll come back tomorrow.